This study aimed to create evidence that could be used to formulate and implement policies by constructing a space for continual deliberations among diverse stakeholders, including patients. In this section, we describe the creation of evidence and methods employed, based on our practical insights and understanding of future challenges. Additionally, we discuss the significance of the space created for deliberation in this study.

Evidence for policy-making generated from the ‘Commons’

Through this study, we generated evidence with regard to two areas: ‘difficulties faced by patients with rare diseases’ and ‘priority research topics in the field of rare diseases’. First, this study revealed a wide range of difficulties faced by patients with rare diseases. This conforms to findings in existing literatures of shared experiences among patients with rare diseases [34,35,36,37,38]. However, topics such as ‘financial burden’, ‘enrolment limitation of private insurance’, ‘inadequate rules’, ‘inadequate infrastructure’, and ‘burden of hospital visits’ are newly presented in this study.

Second, we generated research topics through deliberation to prioritise the field of rare diseases. In particular, the seven research topics listed under the topic title ‘particularly important research topics for strengthening future research on rare diseases’—‘impediments to daily life’, ‘financial burden’, ‘concerns about working and schooling’, ‘anxiety’, ‘pessimism’, ‘mental state specific to genetic diseases’, and ‘burden of hospital visits’—point to desirable research topics that can improve understanding and help create strategies for resolving or reducing burden. Regarding these high-priority research topics, ‘financial burden’ and topics related to psychological issues are also in line with the results of studies reported in the existing literature [12, 47]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the presentation of the following topics as high priorities for research attention is something unique in our research results: ‘impediments to daily life’, ‘concern about working and schooling’, and ‘the burden of hospital visits’. Although the existing literature under the category ‘psycho-social impact’, covers these issues, the present study organises these problems in a different way than in the past, as stand-alone topics, which reflects patients’ perspectives. Moreover, while much of the existing literature lists items related to treatment, prevention, causes, and diagnosis as high priorities [12], none of these was included in the ‘particularly important research topics for strengthening future research on rare diseases’ presented in this study. This is partly related to the decision not to include the criterion, ‘research topics related to life and death’ as a priority research topic in this study on the basis that it has already been addressed with some degree of priority, demonstrating the need for the different perspectives that arise when the lived patient experience becomes a part of the research priority setting discussion.

The research topics were prioritised based on criteria valued more by patients and family members than by researchers and former policymakers (indicated in red in Fig. 6) so as to promote policies and research that prioritise patients’ perspectives. High-priority research topics identified according to criteria on specific important perspectives (shown in red in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively) serve as the basis for promoting research on topics that do not fall into the criterion of ‘particularly important research topics for strengthening future research of rare disease’, namely ‘impact on family’ and ‘difficulties disseminating information’. Thus, this study can optimise priority setting by selecting criteria tailored to the situation and needs of the individuals who will use the results of the priority setting.

Moreover, although the results are only exploratory, the proposed research questions on ‘impediments to daily life’ and ‘anxiety’ were novel concerns for some of the participating researchers, who normally focused on clinical issues and had never thought of them before. This is because the questions were based on the experiences of the patients and family members (i.e. demonstration of their expertise), and the ideas were freely conceived outside the academic field. Although we only proposed research questions as an exercise, the specific difficulties and perceptions of patients and family members were shared with the researchers (some of whom were also clinicians) through discussions on the subject, in a different way from the medical practice and previous workshops on this project. Consequently, researchers have gained significant new insights. To design actual studies in the future, refining the research questions through precise interactions between patients and researchers will be crucial. This is expected to result in novel findings. Furthermore, this process is time-consuming; the process itself leads to mutual learning, as discussed below.

Methods to generate evidence for policymaking in this study

In this study, a space we called the ‘Evidence-Generating Commons’ was established to generate evidence for policymaking. The three main features of the methods are: (1) continual deliberations and co-creation among stakeholders, (2) examinations targeting multiple areas of rare diseases, and (3) outlining three steps for generating evidence.

(1) Continual deliberations and co-creations among stakeholders

Several initiatives are relevant to this study, including PSPs by the JLA, where research priorities are set by stakeholders, such as patients, their families, researchers, and policymakers [26]. In all cases, the time spent on generating results as a single project ranged from a few months to a year. Contrastingly, in this study, we conducted continual deliberations and co-creation for approximately three years. This is because one of our objectives was not to use existing methods, but to create a ‘space’ for generating evidence for policymaking, through practising specific activities by trial and error. Stated differently, patients and researchers created the process by examining the methods that can be used to generate evidence for policymaking in the field of medicine and healthcare. Hence, the method differs from the process of applying established methods for priority setting, such as PSPs.

Therefore, the participants could learn from one another about differences in ideas and perspectives from different standpoints, and trust was fostered through continual communication. Such mutual learning and trust-building contributed significantly to the deepening of discussions in the ‘Commons’. Specifically, during the initial steps, patients and family members took the lead in sorting out their difficulties. However, from the middle of the process, knowledge of ‘what research is’ was shared by the researchers and eventually compiled into an academic paper through the collaboration of both parties. This shows one way of co-creation through the complementary role of expertise drawn from patients’ experiences and researchers’ knowledge.

In developing this new set of methods, the role played by information and communication technology (ICT) is significant, enabling the creation of new communication space. Our ability to conduct over 20 workshops in total, with participants from all over the country, is undeniably a result of internet use. Participants could attend from their living rooms on weekday evenings after they finished work or household chores, or while looking after their children. It also helped busy researchers find time for workshops. The Internet is particularly useful when patients are spread out geographical, especially when organising frequent on-site workshops would be difficult [48]. Holding discussions so frequently likely contributed significantly to the fostering of trust, which is a prerequisite for co-creation.

(2) Examinations targeted at multiple rare disease areas

To date, most studies in the field of rare diseases have been conducted separately for each disease. The PSPs, which are typical examples of a research priority setting as described above, were also generally conducted targeting a single disease.

However, a lack of research resources has been pointed out as a major issue in the field of rare diseases [49, 50], in which cross-disease studies have recently attracted attention [51]. In this study, patients, family members, and researchers from several disease areas participated in a cross-disease study, and it became apparent that the difficulties faced by patients with rare diseases were often common regardless of the specific of the diseases being represented. Our results are supportive of the existing literature on the feasibility of priority setting targeted on multiple diseases [47, 52].

Previous studies have found that priority-setting results are specific to the health and daily life problems faced by patients with a specific disease [53]. However, the results of our priority setting were sufficiently acceptable for all participants with different rare diseases. Some research topics which are uniquely important to individual diseases may not be fully considered as high priority. However, setting a priority for all of the individual rare diseases separately would also be challenging. Therefore, we believe that priority setting for research on rare diseases focusing on multiple diseases would help identify necessary research topics that will positively impact larger numbers of patients. Additionally, patients’ participation in discussions on different diseases enabled them to express their opinion in a way that considered the situations in which patients with different diseases and their families were placed. The participants also could objectively observe diseases related to them, which led to new insights as well as clarification of the ‘characteristics of the disease’. This resulted in the participants’ learning.

(3) Outlining three steps for generating evidence

This study generated evidence in three steps: (i) clarification of difficulties faced by patients with rare diseases, (ii) development and selection of criteria for priority setting, and (iii) priority setting of research topics through the application of the criteria.

In particular, clarifying difficulties enabled us to discuss the issues as something more familiar and imaginable. A significant advantage of this method is the facilitation of agreement among stakeholders with different standpoints and circumstances by dividing priority setting into the steps of selecting and applying criteria rather than directly setting priorities.

However, during the discussions, the way of considering difficulties as research topics was not fully understood. In response to this, additional steps were taken to consider specific research questions. The primary purpose of this additional step was to enhance the patients’ understanding regarding the ‘research’. Indeed, the questions they created accurately represent the patients’ perspectives. Moreover, a short lecture by a researcher on ‘what research is’ was also given, which gradually deepened understanding and led to deeper discussions. Thus, when different stakeholders work together, ‘translating’ to bridge gaps in understanding and knowledge is important.

The value of a ‘space’ for deliberations and co-creations among stakeholders

The process of generating evidence described above also resulted in the establishment of an unprecedented ‘space’ for deliberations and co-creations. Here, we discuss particularly the effects brought to the participants and the versatility of the ‘Commons’.

As described in the results, all participants of the ‘Commons’ experienced positive effects. These effects are in line with previous literature [54,55,56,57]. The project not only led to capacity building for all stakeholders but also created opportunities for interactions, when the participants talked about feelings that were not understood in their daily lives. This positively impacted them, and the ‘Commons’ became an important place for the participants. We are planning a different study to gain a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences, which will be compiled in a separate report.

We also found the versatility of the ‘Commons’. In discussions in the ‘Commons’, as discussed above, opinions were sometimes expressed on measures to solve problems and policy proposals that go beyond setting priorities for research topics. This indicates a gap between the focus of this study on medical research and participants’ expectations of solutions to challenges. Conversely, this also suggests the versatility of the place of the ‘Commons’. We argue that this could be used as a method for deliberative democracy in the future; when stakeholders could be engaged to discuss how emerging technologies should be used in the field of medicine and healthcare.

Discussion on the quality of the evidence generated in this study

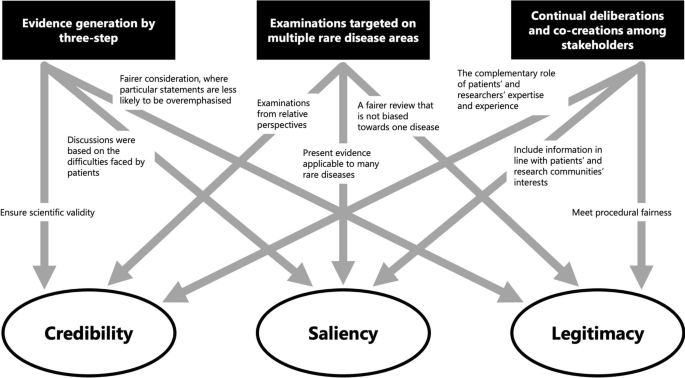

Finally, we discuss the results from a theoretical perspective. We particularly focused on how the methods of generating evidence in this study affected the nature of the evidence generated, in terms of the three attributes of evidence—credibility, saliency, and legitimacy [21, 22]—in policymaking as suggested by Cash et al. and Parkhurst as described above. An overview of this process is shown in Fig. 9.

First, the scientific validity or reliability of the evidence is ensured through a systematic method in three steps. The first step is to clarify patients’ difficulties as a starting point for discussion. Additionally, saliency is enhanced because it includes appropriate information for decision-makers and the audience. Furthermore, the two-step approach to prioritise the development and selection of criteria and the application to set priorities ensures legitimacy by contributing to a fair process in which specific statements do not overly influence the outcome.

Second, targeting multiple rare diseases helps to contribute to the credibility of evidence by encouraging relative perspectives. Further, evidence that can be applied to many diseases is more salient for policymakers, especially in national rare-disease policies, because those that cover only certain diseases are considered inappropriate. Simultaneously, cross-disease examinations also improve the legitimacy of the evidence as a fairer consideration that is not biased towards one disease.

Third, we would argue that continual deliberations and co-creation among stakeholders can generate reliable evidence through the complementary role of the expertise of patients and their families based on their experiences and researchers’ expertise. Moreover, patients’ participation with researchers in the process of generating evidence on various diseases indicates that the generated information conforms to the interests of patients and patient groups facing various difficulties presented in this study, as well as the interests of researchers seeking solutions through research. Furthermore, different stakeholders, such as patients, family members, and researchers from multiple rare-disease areas, were involved in the priority-setting discussions, and more than 20 workshops were held repeatedly to ensure procedural justice.

In terms of salience, current policymakers’ non-participation in the ‘Commons’ may result in insufficient salience for them at present, although former policymakers who participated significantly contributed towards ensuring that the evidence was relevant for policymaking. In response to this, our strategy was not for current policymakers to participate in discussions in the ‘Commons’ from the outset, but to engage in dialogue with them based on information generated from the discussions in the ‘Commons’, and then compile it as final evidence. The strength of this strategy is that it has generated evidence that is more tailored to the needs of patients and researchers and not bounded by existing policy. Conversely, while the possibility of a direct link to policy implementation increases when the study is led by the government, drawbacks also exist, such as directing the study content to some degree and considering consistency with existing policy. Involving current policymakers while maintaining the strengths of this strategy remains a challenge. Certainly, for information generated from discussions in the ‘Commons’ to be demonstrated as effective evidence for policy, it should be referred to in policymaking, although in reality, it is only demonstrated by its implementation in policy. Presently, while information has not yet been demonstrated in the policy field as such, based on Cash’s argument, the three attributes are met and could be considered ‘evidence’.

In summary, the quality of evidence generated by this study was strengthened from multiple aspects. A critical point here is that our approach would enhance EIPM by presenting methodologies for involving patients, researchers, and former policymakers in the policy making process and by fostering knowledge sharing among different stakeholders and consulting target groups to get their perspectives [58].

Furthermore, information produced by stakeholders can be important and valuable not only for policy-making activities but also for a range of activities undertaken by respective stakeholders. For example, important decisions within the respective organisations, such as research funding by patient associations or the setting of research topics by researchers, could be better directed if they are evidenced and reasoned by information that is credible, salient, and legitimate.

Limitations of this study

The main limitation of this study was the small number of target diseases and participants. The study ultimately targeted 10 rare hereditary diseases without curative treatment, and which carry a long-term disease burden. However, all the participants were in a condition and environment that allowed them to participate in the workshops and discuss their issues. Consequently, the views on diseases held by patients who could not participate in such discussions for various reasons were not adequately reflected. However, this does not mean such views are not reflected at all, because family members of patients with rare diseases, such as those with childhood-onset and cognitive impairment, participated in the workshops instead. It was particularly demonstrated that even in the case where patients found it difficult to participate directly in the discussion, their families could participate in reflections and deliberations regarding the patients’ opinions. Furthermore, as this study was conducted using ICT, the impact of the non-participation of those who could not participate in ICT-based settings for reasons such as ICT illiteracy on the results of this study needs to be examined separately.

Add Comment