Description of the invisible fishers project

The IFs project builds on the knowledge that links animal source food (ASF) value chains to reduction of anaemia. The IFs study identified the fisheries value chain as a favorable sector for interventions to reduce anaemia among women in Ghana. Three interventions were considered: The BCC was the first component of the strategies which taught participants about the causes of anaemia and risk reduction strategies, through mobile phone audio messages delivered to women fish processors twice weekly, and a twice monthly guided group discussions including household members. This component (BCC) was part of components two and three.

The second component involved SME + BCC. This component addressed the problem of inadequate fish storage facilities, physical distance from the markets, and inability to access credit facility by providing interest-free loans to women, entrepreneurship training, and daily access to market price information. The third component, FST + BCC, introduced and promoted improved fish-smoking oven called “ahotor oven” designed to reduce women fish processors’ exposure to airborne pollutants associated with fish smoking. Promotional workshops advertising the “ahotor oven” were publicly held in participating communities and program participants were given one-on-one training sessions to enhance product quality. Participants were also offered the “ahotor oven” at a subsidized price, with the option of an incremental payment plan. The overall objective of the project was to develop, adapt, and pilot test a set of interventions within Ghana’s fisheries value chain aimed at mitigating anaemia among women.

The research questions of the study were to examine whether the interventions were able to successfully be implemented, and also examine the extent to which there were changes among the participants in the expected directions in knowledge, behaviours, biomarkers, and exposure associated with the interventions. The study did not aim to assess the impact of the intervention on anaemia, and was not statistically powered to do so. The IFs study only measured changes in anaemia resulting from the intervention, hence the current study conducted cost analysis instead of cost-effectiveness analysis to understand the cost of implementing the interventions for scale-up decision.

Target population

The Invisible Fisher’s Project was implemented among women whose ages ranged between 15 and 49 years and were engaged in fish processing as a primary source of work or activity and had no intention of moving out of the study area. The age range of 15–49 was prioritized because they are the population at highest risk of anaemia due to iron deficiency linked with pregnancies and menstruation [25]. Pregnant women were excluded from participating in the study due to the potential confounding influence of plasma volume expansion on haemoglobin assessment during pregnancy.

Study design and setting

The design of the IFs project was pilot-scaled randomized control trial. The study was conducted in two regions of Ghana-Central and Volta regions between January 2018- November 2019. The two regions are characterized by distinct small-scale fisheries systems (marine and freshwater, respectively) making them suitable in assessing context-specific factors that influence the impact of the interventions on anaemia. The two regions also shared some similarities including strong dependence on local fisheries for livelihood, dominance of smoked fish in the fisheries value chains, the central importance of women processors within these chains, market constraints among small-scale processors, and a high burden of anaemia among women.

Sampling

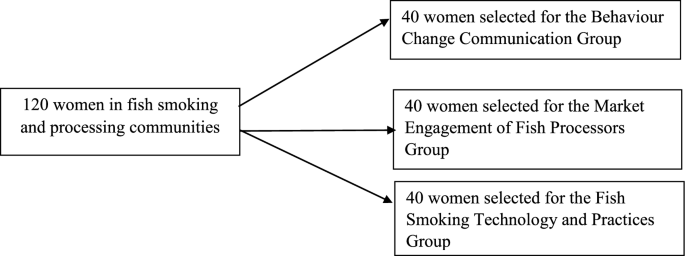

In each region, six communities were purposely selected for participation. Each community consisted of ten participants, thus a total of 60 participants were selected from each region. In total, 120 women were selected from a total of 12 communities across the two regions.

Two communities in each region were assigned to one of the three treatment arms. Ten women in each community were purposively selected for participation to ensure intra-community variation on participant’s age, socio-economic status, years of experience with fish smoking, and the scale of fish smoking enterprises (Fig. 1).

Methods for the costing study

Study design

The design of this study was a descriptive cross-sectional design that used the ingredient-based approach to estimate costs.

Data collection

Both financial and economic costs were estimated. Financial cost refers to the direct cash expenditure on goods and services that were incurred in undertaking the Invisible Fishers project. Economic costs or opportunity costs on the other hand, were the alternative uses of resources that have been forgone for using it on the implementation of the project. The concept of economic cost or opportunity cost recognizes the cost of using resources as those that are unavailable for productive use in other competing intervention programmes. The economic costs is made up of direct costs plus indirect costs. All costs were identified, measured prospectively, and valued at 2018 prices to represent the costs of the IFP. Costs of items that were expressed in Ghana cedis (GHC) were converted to the United States dollars (US$) at an annual exchange rate of GHC 4.59 = US$1 for Bank of Ghana 2018 expenditure year. Costs relating to research were excluded, as this did not form part of the core implementation activities.

Data on time spent by volunteers and women participating in the intervention were obtained using structured questionnaires and project records. This information was used to estimate the direct and indirect costs of volunteers and women participants. In all, there were 12 volunteers on the entire project, however one volunteer dropped out of the study. Four volunteers, each were assigned to the BCC, and SME + BCC interventions, whilst three volunteers were assigned to the FST + BCC intervention. Financial records of each intervention were obtained from receipts, invoices, and other financial records kept by the finance officer. Records from the general project administration were also reviewed to reconcile information from the interventions where inconsistencies were identified in the records kept by finance officers of the intervention.

The activities that were costed in the intervention implementation are indicated in Table X (Supplementary file 1).

Cost analysis

Costs were analyzed from the societal perspective, which means that cost to all those involved in the intervention implementation were estimated. These included costs to the implementers of the project-University of Ghana, University of Michigan, Innovation for Poverty Action, Netherland Development Organisation, and VIAMO mobile, the women fish processors, caretakers of women fish processors, and community volunteers who donated their time in the implementation activities but were not remunerated. The cost of time for women fish processors, community volunteers, and caretakers were evaluated based on the daily wage rate of their work. Staff of the implementing institutions were paid based on the equivalent of the daily wage rate earned in their formal work. The time horizon for the intervention analysis was 18 months, which was the period for the intervention implementation.

Financial and economic costs were analysed separately. Financial cost represents the actual costs of items and services purchased; thus, costs are described in terms of how much money has been paid for the resources used in the project. The financial cost is usually estimated from the payer’s perspective, and costs are resources forgone by the payer. The financial costs estimate the price and quantities of the resources for the project. There are different ways financial costs can be classified- by inputs, activity, level, etc., among others. For this study, financial costs classification was by inputs, mainly considering the lifespan of the items bought and by activity. These include capital and recurrent costs. Capital costs items are those that last longer than one year, and examples include building, oven, vehicles, equipment, and training that usually happens once for the entire duration of the project. Recurrent costs are the cost of items that are used up in the course of a financial year and are usually purchased regularly. Recurrent costs are the running costs of the programme. Examples of recurrent costs include personnel, supplies, building operation and maintenance, recurrent trainings, etc., Adding capital costs and recurrent costs constitute total financial costs. Specific cost items in this study that were estimated under financial costs included oven costs, personnel, transportation, training (recurrent), meeting, field accommodation and office space, among others.

Economic costs or opportunity costs on the other hand define costs in terms of alternative uses that have been forgone by using a resource in a particular way. It means the cost of using resources, as these resources would not be available for productive use elsewhere. The economic cost is the broader way of defining costs. This cost refers to the resources forgone by all society. It is important to note that analyses using economic costs do not replace those using financial costs but supplement them with additional information useful for decision-making. Examples of economic costs include time spent by community volunteers, and donated goods and services. The main economic cost items estimated in this study were the time of community volunteers, women fish processors, caretakers, and the economic cost of capital items.

Resource use was measured based on scheduled activities for each intervention. Financial records were assessed and analyzed to identify and categorize the expenditure of each intervention, representing different activities. An inventory list was created for the various types of resources utilized, and these resources were organized into different cost categories. Costs were classified by resource inputs (capital vs recurrent) and indirect costs. All capital items were depreciated using a discount rate of 3% as this conforms to the rate usually applied in global health evaluations in both developed and developing countries. For depreciation of capital items for the economic costs, the annualization method was applied using the discount rate, the useful life of the capital item, and the annualization factor. The annual financial cost of depreciation for capital items on the other hand, we used the straight-line depreciation method to estimate annual rate of depreciation. This involves identifying the capital cost items, estimating the replacement costs and years of useful life, and finally dividing the replacement costs by the number of years of useful life.

The life span of “ahotor oven”, a locally manufactured oven for smoking fish used in fish smoking technology arm was estimated to be 10 years, based on information received from the manufacturers. An average useful life span of three years was assumed for all office equipment, such as computers, printers, office furniture, and mobile phones [26].

Recurrent costs and capital costs were estimated and summed up to constitute financial costs of the interventions. The allowance paid to community volunteers engaged in the implementation activities was added to the recurrent costs of the respective arms.

Data on indirect costs comprised both volunteers’ and women participants’ time and productive losses, that is the number of workdays lost for participating in the intervention activities. The questionnaire for the indirect costs revealed that total time required to perform activities of each intervention including meeting time, caretakers time, travel time varied among the three interventions based on the number of activities performed in each arm.

The time for women participants and community volunteers were valued based on the reported local wage rate in a month within the intervention communities. The reported monthly wage rate for women fish processors from their fish processing work was used to estimate the value of their time. It was assumed that women fish processors and community volunteers worked for 8 h daily per 6 days in a week. The 6 days in a week was used typically because women worked from Monday to Saturday, whilst Sundays were used for church and other household activities. The value of a woman participant’s time was calculated as the number of hours on the project multiplied by the minimum hourly rate per day and week. This same approach was used for calculating volunteers’ time. The hourly income rate for women fish processor was estimated to be US$5.95 (GHC23.79). Monetary value or equivalent of workdays lost was estimated by multiplying the number of workdays lost by the hourly wage rate for women fish processors and volunteers within the intervention communities. Summation of capital and recurrent costs constituted financial costs, whilst financial costs plus indirect costs represented the total economic costs of the project.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken, varying key cost indicators which had some degree of uncertainty to test the robustness of the cost estimates. Key cost indicators that were varied included discount rate, wage rate, and life expectancy of capital items.

Firstly, one-way sensitivity analysis was performed using lower (2%), and higher (5%) discount rates in calculating capital costs. Secondly, 5 years, 8 years and 12 years useful lives were assumed for all equipment, furniture, and ahotor oven, respectively, instead of the base years. Thirdly, the national minimum wage rate of GHC11.82 was used to value all volunteers time in place of the local wage rate of the communities involved for the economic costs analysis. In addition, during the project implementation, community volunteers participated in the intervention activities but were not remunerated for their services. In view of this, it was assumed in the sensitivity analyses that community volunteers were given allowance equal to their indirect costs. Finally, a multi-way sensitivity analysis was performed using four different scenarios, varying multiple parameters at the same time. For scenario one, 10% discount rate, and national minimum rate were used to estimate the effect on economic costs; scenario two used 10% discount rate, and higher useful life span of capital items than the base case (5 years for equipment, 8 years for furniture, and 12 years for ahoto oven). Scenario three used 5% discount rate, and the assumption that indirect cost of time was the same as allowances paid to volunteers; whilst scenario four used 10% discount rate, national minimum wage, and indirect costs of community volunteers were assumed to be the same as allowances paid to them.

Add Comment