Quantitative results

Overall, 649 patients completed the questionnaire. According to the study findings, the research subjects were mainly middle-aged individuals who were identified as Kinh and did not follow any religion. Notably, women with a high school education constituted a significant portion of the study population, with more than half of the participants falling under this category and earning an average income of more than 5 million VND. Of the patients, half had previously undergone breast cancer screening. Most of them did not have relatives who had breast cancer (84.9%) (Table 1).

Breast cancer screening motivation

Table 2 showed that the mean breast cancer screening motivation score observed among participants was 3.55 ± 0.55. In particular, the average scores for external regulation, autonomous regulation, and introjected regulation were 3.71 ± 0.56, 3.56 ± 0.59, and 3.52 ± 0.73, respectively. Women had a lower average score for introjected regulation (3.2 ± 0.69).

Multiple linear regression

Table 3 presents the results of a multivariate linear regression model that was performed to identify factors associated with breast cancer screening motivation and subscale scores. According to the parameters of the multiple linear regression model, breast cancer screening motivation was explained significantly by ethnicity, having regular health check-ups, a family history of breast cancer, regularly receiving information about breast cancer, and having a woman’s health issues in the past, with a direct relationship between these variables. Ethnicity, religion, regular health check-ups, and having a woman’s health issues were positively associated with autonomy. Having relatives who had breast cancer and having a history of women’s health issues were positively associated with introjected regulation (p < 0.05). Ethnicity, having regular health check-ups, a family history of breast cancer, and regularly providing information about breast cancer were strongly associated with external regulation (p < 0.05). Amotivation was related to having relatives who had breast cancer and having a history of women’s health issues.

Qualitative results

This study highlights the importance of breast cancer screening for women in Vietnam. Table 4 highlighted that participants were between 25 and 75 years old, and the mean age was 45 years. Over 60% of the participants held high-level degrees, while the rest either finished high school or had not yet graduated. Most of the women were married and employed as homemaker.

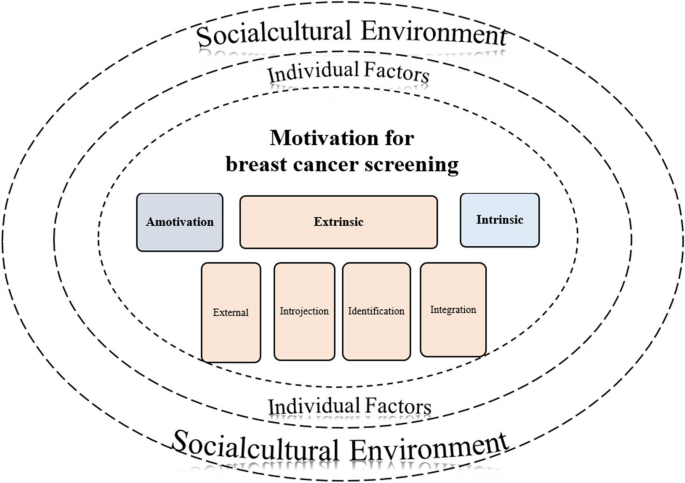

After conducting a thorough analysis, authors identified three categories of motivation based on self-determination theory: amotivation, intrinsic motivation, and extrinsic motivation. Factors that impact an individual’s motivation for screening were categorized into two groups: individual and sociocultural factors. In addition, the following factors influenced the motivation for breast cancer screening, as shown in Fig. 1.

Motivation for breast cancer screening

Intrinsic motivation

Participants exhibited their innate motivation to maintain their well-being by regularly undergoing breast cancer screening, which reflected their intrinsic motivation. This practice was not contingent on external demands, as women may even unconsciously engage in it. According to the participants’ experiences, this screening was often conducted individually or integrated with other self-care activities, such as bathing or massaging. This intrinsic motivation was typically more evident in the case of breast self-examination than in the case of other screening methods.

Participants shared that “I do it every day, I check it when taking shower” (ID10, 52 years old, Bachelor’s degree) and “I have been doing it for a long time, it is like it is my lifestyle, well… and it is also regular” (ID08, 36 years old, Bachelor’s degree).

Extrinsic motivation

A variety of extrinsic motivations for breast cancer screening, including external, introjection, identification, and integration, emerged from the data. The extent of volition increased from external to integration regulation and became closer to intrinsic motivation. The present discourse expounds on the phenomenon whereby volition transitions from external regulation to integration regulation and attains proximity to intrinsic motivation. The detailed information is described below.

External

Providing favorable screening conditions such as insurance or agency and organizational support has proven to be essential in facilitating women’s access to screening services. Furthermore, government-supported screening programmes play a crucial role in encouraging women to undergo screening by giving them opportunities to do so. Women who might not have considered screening earlier, who participate in the program when they receive support and who are free. Although there could be other factors that influence their decision, in general, they did not feel the intention to undergo screening until they were offered support. Alternatively, they might undergo screening under pressure from those around them. Participants highlighted, “My insurance covered 100 percent, so why do not I go see a doctor? It will not cost you money” (D12, 41 years old, High school diploma); “If the doctor tells me to stay at home, I need to check it from time to time, so I will just do it” (D11, 48 years old, Bachelor’s degree); My mother, she often worries, also often tells her children, as women, to check this and that. Sometimes, she asks, “I told you so, have you gone to check yet?” (D13, 38 years old, High school diploma).

Introjection

Introjection occurred when the participant feft a danger or problem that was personally relevant and began to change from within. Breast cancer is increasingly common, and the risk of cancer is very high. In addition, some participants shared that they had experience with breast cancer and its consequences. Therefore, they started doing screening consciously and intentionally. Some women shared, “I feel cancer is getting more common among younger adults, not like in the past, only a few people got it” (D03, 35 years old, High school diploma).

Identification

Women were motivated to undergo breast cancer screening not only for their health but also for the sake of their behavior and well-being. The emphasis was on their own values, awareness of the effectiveness of screening, and a desire to take proactive steps in ensuring a healthy and worry-free future. This type of motivation reflects a self-driven commitment to maintaining good health and enjoying life without the burden of potential diseases such as breast cancer. One woman mentioned, “Then, I think about my health. Now health is gold. If I live for myself, I have motivation.” (D13, 38 years old, High school diploma): “In the past, breast cancer was an incurable disease, but now, if detected early, it can be cured, so we have to regularly screen for it” (ID08, 36 years old, Bachelor’s degree).

Integration

Participants might initially be motivated by external factors; however, through a process of internalization, they begin to adopt these motivations on their own. This could result in a motivation that was unified with intrinsic motivation, meaning that the individual now engages in the behavior because they truly value and identify with it. Therefore, this approach leads to a sense of autonomy and self-awareness in individuals’ pursuit of behavior. Those women believed that they were screened because of their role as mothers or wives in the family; because of their support for their children; because of setting examples for other women; or because they want/have to be proactive and independent in life as well as because they comply with personal principles. In addition, they are people with a special interest in health care, not only for themselves but also for those around them. In particular, when they strongly believe in the effectiveness of screening and screening because of the spiritual value it brings. Women who engaged in behavior for reasons that went beyond the actual benefits of the behavior and related to what is most about themselves or their lives. Some women shared their story: “It (screening) brings two different spiritual values. When I have done my best, but it does not work, I’m satisfied. If I do not do anything, I feel regretful. because I have not done it yet”” (D09, 60 years old, Bachelor’s degree); “I am the main breadwinner for the family… but… (now) I only have 3 children left, and if something happens to me, my children will suffer.” (D12, 41 years old, High school diploma).

Amotivation

Amotivation is a phenomenon characterized by a lack of motivation among women to undergo cancer screening or even express an intention to do so. This lack of motivation could be due to their strong belief in their own good health, which led them to ignore the importance of screening. Additionally, being overly subjective about the potential results or consequences of a breast cancer diagnosis could also contribute to amotivation. A 35-year-old woman said, “I am still young, I don’t care (breast cancer screening) because sometimes I am also confident about my health” (D03, 35 years old, High school diploma).

Factors influencing breast cancer screening motivation

The importance of women’s motivation for their ability to undergo the screening process and maintain it over time. The factors impacting motivation included individual, and sociocultural factors.

Individual factors, including emotions, and personal experiences could influence women’s motivations and decisions regarding breast cancer screening. Emotional states could play a significant role in shaping attitudes and behaviors, including a range of emotions such as anxiety, shyness, curiosity, optimism, and even phobias related to breast cancer and a willingness to undergo screening. Personal experiences related to breast cancer and diseases, such as age, menopause status, previous experiences with screening, in general, could impact screening decisions. Discomfort or pain during mammography may discourage women from screening, leading to avoidance of early detection benefits. The inconvenience and potential delays associated with crowded public hospitals could contribute to a decline in motivation to prioritize screening. Furthermore, previous health experiences could shape an individual’s perspective and attitude toward healthcare practices. These challenges create barriers that discourage women from accessing essential screening services, impacting overall screening rates and potentially resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment.

Some stated “I am old and need to pay more attention to my health as it can impact my children and grandchildren if I get sick.” (D14, 63 years old, High school diploma); and “when I go for a genital or breast exam, I don’t want to go to the doctor because I’m shy, really embarrassed”.” (D02, 32 years old, High school diploma).

The sociocultural environment encompasses a range of beliefs, attitudes, and societal pressures that could shape women’s motivations for breast cancer screening. Societal perceptions and beliefs regarding diseases are specific to women and girls; folk beliefs, such as those related to “trái chàm”; beliefs about abnormalities and visiting the doctor; acceptance of fate and perception that having cancer means inevitable death; and modern life with myriad pressure that contributes to hesitation or avoidance of screening. In contrast, the widespread availability of online information could empower women to make informed decisions about their health and remind them about breast cancer and screening. Some mentioned: “I believe that when Heaven appoints, man must obey” (D12, 41 years old, High school diploma); “The old ladies said that if you have “trái chàm”, you will easily get cancer” (D09, 60 years old, Bachelor’s degree).

Add Comment