Participants

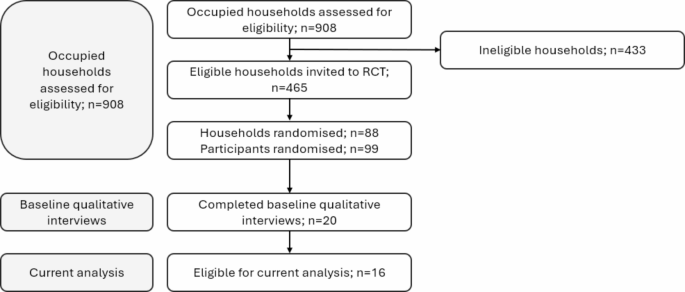

Figure 1 displays participant recruitment in the context of the RCT. Of the 99 participants in the RCT, 20 of the invited subset completed baseline interviews. 16 participants completed at least one follow-up and were eligible for this analysis. Ten participants completed three interviews and six participants completed two interviews, making a total of 42 interviews included in this analysis (Baseline, n = 16; 3-month, n = 15; 6-month, n = 11). Table 2 presents demographic details of interview participants collected at baseline.

Summary of common mechanisms identified

We identified six common mechanisms that facilitated modal shift in response to a diverse range of key events. We take each of these mechanisms in turn and describe the key events that led to a change in contexts and the individual and environmental contexts that influenced whether a change in travel mode change occurred. Table 3 describes the generalisable configurations identified. Using an illustrative example, when a bus cancellation (key event) occurs in a context where (i) an individual had planned to use the bus to commute, (ii) they are not able to work from home and are required to be at work on time (for example, a teacher) and (iii) they have access to a car, this leads to a modal shift from bus to car (outcome). The reasoning (mechanism) is that access to the planned transport mode has been removed and the individual is unable to reach the destination on time, leading to a deliberation process and the selection of an alternative mode.

Changing access

Reduced access

When access to a transport mode was reduced or removed and the planned mode was unable to transport participants to their destination, modal shift was dependent on available alternative modes and characteristics of the planned journey. The key event that reduced access to the existing travel mode triggered modal shift in contexts where the journey was necessary and there was an acceptable alternative mode available. For example, ‘Yesterday I was not allowed on the bus going into work in the morning and I wasn’t the only one, there were about 15 or 20 other people who couldn’t get on the bus because it was full, and where they’ve changed the timetable, the next bus isn’t for another half an hour after that, so I wouldn’t have got to work on time, so I had to drive (P0811)’. We observed examples of events that reduced access to the bus through acute cancellations, occurring due to timetable changes, driver strikes and adverse weather; and that reduced access to the car when ‘my car was having its service done (P0371)’, participants had been drinking alcohol, or car parking was unavailable at the destination.

In contexts where travel was required but there was no acceptable alternative mode available, participants implemented alternative strategies which included staying overnight at the destination, changing travel route or time, or taking annual leave because it was not possible to get to the workplace: ‘I used to be a 9 to 5.30 person. Since using the [local bus service] I’ve changed to being an 8 to 4.30 person just to avoid the rush hour traffic (P3291)’. This was evident among people without access to a car who used the bus. Where there was no alternative mode available and the journey was not necessary, participants simply did not travel or, where flexibility allowed, worked from home.

Increasing access

Some key events led to increased access to alternative travel modes. These included new jobs or colleagues moving to Northstowe. Modal shift occurred among participants who had new jobs when the new workplace was accessible by an alternative travel mode, generating a new stable context with potential to facilitate longer-term modal shift. In some cases, however, the alternative travel modes described would not have been feasible for everyone (for example, not everyone can realistically run to work). For others, meanwhile, both the original and new work locations were accessible only by car, and despite exploring alternative options no modal shift happened for those participants.

Changing reliability

Reducing reliability

The ongoing reduced access led participants to reason that they were unable to rely on those transport modes for consistent journey times that enabled them to arrive at the destination on time. Within this study, the ongoing bus cancellations and overcrowding was sparked from wider contextual changes influencing the transport infrastructure. Participants reported that Britain’s exit from the European Union, led to HGV driver shortages, resulting in a shift of bus drivers to HGV driving leading to an acute shortage of bus drivers and a reduced bus timetable. Once again, modal shift occurred in contexts where reduced reliability affected the existing travel mode and within the context of journeys that were time dependent, for example, travelling to an airport or repeated journeys such as the commute: ‘On a number of occasions either the bus hasn’t turned up because it’s been cancelled, or I’ve not been allowed on because it’s been too full … I think the last interview was close to the point at which I just stopped using the bus altogether because I couldn’t rely on it (P0811)’. The repeating nature of journeys exposed individuals to the ongoing unreliability which they viewed as disruptive. It was notable that tolerance towards reduced reliability was variable and affected by weather and sustainability values. For those making journeys infrequently or leisure time journeys that were not time dependent, unreliability did not seem appear to trigger modal shift.

Faced with deterioration of the reliability of the bus service, participants who had no alternative travel mode were unable to immediately switch mode. However, the consequences of unreliable bus travel affected their ability to arrive at work on time: ‘I usually reach five to ten minutes late … despite all the running I do (P1291)’. This triggered participants to seek alternative travel modes, such as purchasing bikes and learning to drive for those who were physically and financially capable: ‘My experience for the past two months have kind of like proven that the busway’s not very reliable with regards to time. So I would still gear towards having at least a car for the household, just for the situations when I have to get somewhere on time (P1281).’ One participant’s coping mechanism was to change to a job not in line with their career goals in order to cope with the unreliability of the bus service.

Improving reliability

Restoration of the bus timetable resulted in a more reliable bus service which reversed the reasoning described above: ‘it is now my intention to try and use the bus again going forwards and from that one experience I had it does seem to have made things a little better (P0811)’. In the case of the bus, improving reliability triggered a modal shift among participants whose travel preference was the bus and who were aware of the improvements. We noted a difference in timing returning to bus travel dependent on sustainability motivations, whereby participants with stronger motivations were more eager to restore bus travel.

Changing financial cost

Increasing financial cost

We found that modal shift occurred when participants were faced with rising travel costs, resulting in this study from rising petrol costs linked to global fuel prices, coupled with increased frequency of office working following lifting of covid-19 restrictions. Participants who changed travel mode reasoned that the cost of their current travel mode was becoming intolerable and sought cheaper alternatives. Modal shift occurred in the context of commuting journeys which were required and where cheaper and acceptable alternatives were available. For example, one participant initiated a car share with a colleague who lived nearby, sacrificing the convenience of being a sole car user to reduce journey costs.

In a context in which individuals believed they were already travelling in the cheapest way, no modal shift occurred, but as one participant noted ‘I’m so glad I’m car sharing because it’s like £10 more expensive to fill up my car (P1191)’. Furthermore discretionary journeys, for example to eat out at restaurants, did not appear to be subject to modal shift. Instead, participants chose not to make these journeys.

Reducing financial cost

We identified one event that reduced the financial cost of travel: ‘They’ve [bus company] introduced some flexible fares that mean it’s very economical, it works out at £2.94 a day for bus travel, which is definitely cheaper than petrol (P0811)’. When this occurred simultaneously with increased commuting frequency described above, the cost difference was amplified and the participant reasoned that bus travel was the cheapest mode and modal shift occurred from the car to the bus. In this context, the participant was actively seeking alternative travel modes due to the cost of using the car. We saw no instances of modal shift due to the reduced bus fares among participants who were unable to use the bus for commuting. Among participants already using the bus, the reduced cost was welcome and while no modal shift occurred, the reduced cost may have contributed to maintaining that travel mode.

Changing convenience

Convenience to meet changing demands of dependents

We noted instances where the key event led to changes in the convenience required of travel due to the demands of dependents. Where this required greater convenience (e.g. the acquisition of a new pet) and an alternative mode provided greater convenience, modal shift occurred. For example, shifting from car-sharing to sole car use enhanced the flexibility to leave work early, or switching from walking to car use decreased the journey time. In contrast, when the key event reduced the need for convenient travel – because a participant’s child was starting school near home, and no longer travelled to with her to the workplace nursery – intentions were formed to travel by bus.

Increasing confidence

We found that prompts to encourage individuals to try alternative travel modes, including suggestions from friends – ‘She [friend] said, do you want to walk or shall we cycle? So I said, no, let’s cycle (P2591)’ – or workplace initiatives, resulted in a modal shift towards the bicycle. This shift happened among nervous cyclists when there was social support in place and cycling equipment was available in the wider environment, via spare bicycles or local cycle hire schemes. The social support increased participant confidence that they were capable of cycling. When similar prompts were experienced by nervous cyclists without social support, modal shift did not occur and the participant did not trial cycling, despite the availability of cycling equipment in the local environment.

Raising awareness

Raising awareness of pro-environmental behaviour

Finally, we observed modal shift from the car to walking or cycling for journeys to complete short errands (e.g. posting letters, visiting doctors) due to an enhanced awareness of the environmental impacts of car use and the health benefits of active travel. ‘I don’t use the car quite so much. I’m either not going anywhere or I’m walking … so I do try and not use it . .because it’s better for me to just to walk everywhere (P2691)’. These participants reasoned that their current car use did not align with their view on environmental impact, and therefore changed mode. Both participants had sufficient time to complete these journeys, and the proximity of the errands to their homes enabled these journeys to be completed via walking or cycling.

Common principles

Across the six mechanisms, we identified three notable commonalities. Firstly, when key events disrupted existing travel modes, they often led to changes in travel modes because participants were required to consider alternative travel modes. For example, two participants reported changing their travel mode when their car was in the garage, reflecting a disruption in their current patterns of car use for commuting or errands. In contrast, when events acted on travel modes not currently used by participants they had little influence on their travel choices. For example, deterioration of the bus service was not reported to influence car users’ choice of travel mode. Secondly, we identified the availability of alternative modes and the journey characteristics as important contextual influences. Changes in travel mode were only observed where there was a suitable alternative mode available. In the absence of a suitable alternative participants continued their current travel patterns, although we did observe them forming intentions to increase the availability of alternative modes, by obtaining a driving license or purchasing a bike. We identified the characteristics of the journey as an important context and participants’ travel choice was different dependent on whether a journey was discretionary, necessary or time-dependent. Thirdly, we observed that the experience of the new travel mode played an important role and positive or negative experiences of the alternative mode informed future travel intentions. For example, one participant described a pleasant experience of cycling after commuting as part of a workplace sustainability day, citing the sunset and social aspect as enjoyable aspects that prompted intentions to continue with this mode.

Add Comment