Ovarian Brenner tumors can occur at any age, with a higher prevalence among postmenopausal women, affecting approximately 80% of patients over 50 years old. Benign alterations typically manifest unilaterally, with a predilection for the left ovary. Approximately 5% to 14% of ovarian MBTs present are bilateral, and the risk of malignancy increases with age among women with ovarian Brenner tumors [5]. The findings of this study are consistent with these observations. MBTs represent a highly uncommon subtype of ovarian epithelial tumors. The precise incidence of MBTs remains unclear, with existing research primarily comprising case reports and small-scale case studies. Conversely, primary ovarian squamous cell carcinoma is exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.5% of ovarian cancers. In the 2020 WHO classification, ovarian squamous cell carcinoma is classified as a somatic-type tumor originating from teratomas. As the majority of cases arise from the malignant transformation of mature cystic teratomas, accounting for 80% of cases of teratoma malignant transformation [6, 7], with a minority possibly developing from Brenner tumors [8]. Studies have found an association between HPV infection and reproductive system tumors, particularly cervical cancer. Additionally, Svahn et al. [9] found that 15% of ovarian epithelial cancers were associated with HPV infection, with a higher prevalence in Asian regions. The carcinogenicity of HPV has been confirmed in various tumors, with recent research suggesting that HPV establishes persistent infection through the post-infection microenvironment, thereby inducing cervical epithelial dysplasia [10]. In the present case, the patient had a history of HPV infection and Brenner tumor, suggesting two factors associated with the development of ovarian squamous cell carcinoma. Combining the aforementioned literature, this case report may provide a basis for studying the reasons for the occurrence of ovarian squamous cell carcinoma.

Current research suggests that the clinical symptoms of ovarian Brenner tumors are similar to those of other epithelial ovarian tumors, with the most common being abdominal mass and distension, followed by abdominal pain and postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, and constipation, while some patients may be asymptomatic [11]. Combining the findings of this study indicates that the clinical symptoms of ovarian Brenner tumors lack distinct specificity and are associated with patient comorbidities, tumor size, and malignancy. Approximately 25% to 36% of Brenner tumors may be associated with other benign ovarian tumors, such as serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenoma, and teratoma, possibly due to hormone secretion by Brenner tumor cells, leading to local cellular proliferation [12]. In this study, 40% of cases were associated with other benign ovarian cysts, slightly higher than reported in the literature, although the sample size was small and requires extensive data analysis to verify. Ovarian malignant tumors are often challenging to detect in early stages, with over 85% of patients diagnosed at advanced stages. The five-year survival rate for early-stage lesions can reach 90% [4]. However, a survey conducted in Italy indicated a decrease in quality of life and changes in sexual activity among gynecological cancer survivors [13], emphasizing the critical importance of early detection and treatment of ovarian lesions. The lack of distinct clinical symptoms in ovarian Brenner tumors often leads to delayed diagnosis, with clinical symptoms frequently attributed to other conditions, necessitating postoperative pathological diagnosis. In this study, 13 out of 20 cases underwent surgical treatment due to pelvic masses or other reasons, with Brenner tumors incidentally discovered postoperatively.

Regarding tumor markers, there are currently no specific indicators. It has been reported that approximately 70% of patients with MBTs exhibit elevated levels of Cancer Antigen 125 (CA125), which gradually decrease to normal levels after treatment and increase again after recurrence [5, 14]. However, in this study, CA125 levels were normal in all 19 cases of benign Brenner tumors. Three cases of benign Brenner tumors showed elevated levels of Squamous Cell Carcinoma Antigen (SCC), excluding one case of cervical cancer, and one case showed an increase in Carbohydrate Antigen 153 (CA153). In case 20, when malignancy occurred, CA125 and CA153 levels were slightly elevated, while SCC and Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) levels were significantly elevated, with the most significant increase observed in CA199. CA199 is typically synthesized by normal glandular epithelial cells, such as pancreatic and bile duct cells, as well as epithelial cells of the stomach, colon, endometrium, bronchi, and salivary glands. Clinically, elevated levels of CA199 are initially associated with digestive system diseases, particularly malignant tumors. CA199 levels are elevated in malignant ovarian tumors, especially mucinous ovarian tumors, although the diagnosis of ovarian tumors lacks specificity [15, 16]. Qian et al. [17] reported the first case of abnormally high serum CA199 levels in a transitional Brenner tumor in 2022. This study also presents a unique case of significant CA199 elevation, although the patient had concomitant ovarian squamous cell carcinoma, suggesting a possible association. Chiang et al. [18] demonstrated that SCC, CA125 and CEA, among the tumor markers of primary ovarian squamous cell carcinoma, were elevated in the peripheral blood of many patients, which were related to the therapeutic effect and prognosis of the disease. Case 20 supports this view, indicating that if CA125, CEA, and SCC Ag levels are elevated, the possibility of ovarian squamous cell carcinoma should be considered. When CA199 levels are abnormally elevated without reasonable explanation, the possibility of ovarian Brenner tumor should also be considered. Combining three cases of elevated SCC and one case of elevated CA153, which normalized postoperatively, whether SCC and CA153 can assist in diagnosing Brenner tumors and warrants further investigation.

The typical ultrasound appearance of ovarian Brenner tumors is termed the “shell sign” [19] characterized by a strong echogenic mass in the anterior part of the tumor with marked sound attenuation in the posterior part, but no obvious blood flow signal within the mass. In this study, the ultrasound findings of three cases of simple ovarian Brenner tumors closely resembled the typical shell sign (see Fig. 1A), although this appearance can also occur in other solid ovarian tumors. Our ultrasound findings suggested the possibility of fibroma or teratoma, lacking specificity. After contrast-enhanced CT imaging, it has been reported that benign ovarian Brenner tumors show mild enhancement, while lesions of MBTs exhibit moderate to high enhancement [20]. In this study, ultrasound and contrast-enhanced CT imaging of case 20 at malignancy presentation displayed similar features to other epithelial tumors (see Fig. 1B-E). Additionally, four cases of benign ovarian Brenner tumors underwent pelvic-enhanced MRI, with no apparent blood flow signal observed and no significant enhancement or only mild enhancement after contrast, indicating that ultrasound, contrast-enhanced CT, or enhanced MRI cannot provide specificity for diagnosing Brenner tumors but can serve as reference indices for distinguishing between benign and malignant tumors.

Reportedly, Brenner tumors exhibit hormonal activity, with oestrogen considered the primary hormone secreted by these tumors [21]. This, in turn, may lead to endometrial pathologies such as endometrial hyperplasia, occurring in 4% to 14% of cases [22]. In this study, only 2 cases showed elevated oestrogen levels, yet they presented with concomitant endometrial carcinoma, irregular endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial polyps, and abnormal uterine bleeding, suggesting that ovarian Brenner tumors may cause oestrogen abnormalities, thereby leading to endometrial-related diseases.

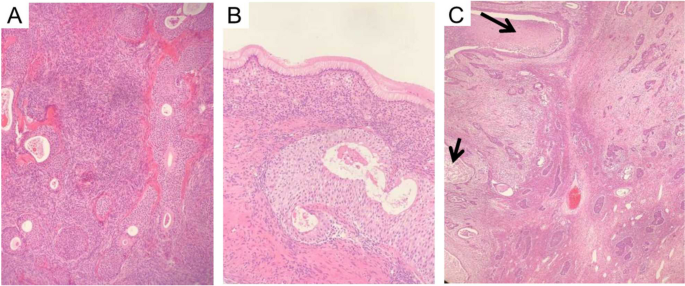

All cases underwent pathological diagnosis. A typical case, Case 20, first presented in 2012 with a benign Brenner tumor on the left side. It recurred and evolved into MBT in 2017, five years later. Our hospital’s pathology department reflected on whether malignant components were missed in 2012 and reviewed the slides from that year. The distinction between benign and malignant ovarian Brenner tumors lies in the degree of cellular atypia and the presence of stromal infiltration. Benign Brenner tumors of the ovary typically consist of solid components, with tumor cells forming oval or irregular nests scattered within fibrous stroma. Nutrient-poor calcification and glassy changes can be observed within, with cell nuclei being oval or round, showing no obvious atypia [23]. Ovarian MBT histological characteristics include increased layers of tumor cell nests (Fig. 2A, B), deeply stained cell nuclei, polymorphism, and evident nuclear division activity (Fig. 2C), with the appearance of pathological mitotic figures and stromal infiltration [23]. Several related gene mutations may be associated with ovarian MBT, inducing the gradual progression of benign ovarian Brenner tumors to ovarian MBT [24, 25]. Therefore, gene mutations are associated with deterioration, and genetic testing may be considered in subsequent treatment.

Pathological picture of Case 20. A Case 20, 2012 Benign Brenner Tumor: Within the dense fibrous stroma of the ovary, oval or round-shaped nests of transitional cells were observed, exhibiting mild cellular morphology. Some nests showed cystic changes, lined with mucinous epithelium, with eosinophilic material seen in the center of the cysts. Magnification: 100x. B Case 20, 2012 Benign Brenner Tumor: At the lower end of the transitional cell nests, tall columnar mucinous epithelium was visible. Magnification: 400x. C Case 20, 2017 MBT with Squamous Cell Carcinoma Component: The epithelial nests of the tumor were irregular, with partial cystic dilatation on the left side containing abundant necrotic material. The epithelial cells exhibited marked anisocytosis, prominent nucleoli, and focal keratinization. Inter-cellular bridges were observed, indicative of squamous cell carcinoma (indicated by arrows). The nests on the right side varied in size, with irregular margins, crowded cells showing marked anisocytosis, increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, thickened nuclear membranes, prominent nucleoli, and visible mitotic figures. In the background ovarian stroma, infiltration of acute and chronic inflammatory cells was observed, consistent with MBT. Magnification: 40x

The primary approach for treating ovarian Brenner tumors remains surgery. Due to the patients’ advanced age, often in perimenopause or postmenopausal, adnexectomy serves as the main treatment for benign Brenner tumors, effectively reducing recurrence rates [26]. Similar to other epithelial ovarian cancers, the initial treatment for MBT is tumor-reducing surgery. In our study, MBT underwent standard staging surgery for ovarian cancer, but the role of lymph node dissection (LND) in this rare cancer subtype remains unclear. Recent research indicates no significant difference in disease specificity or survival rates between patients who underwent LND and those who did not, with only 5% of patients who underwent lymph node sampling showing lymph node metastasis [12]. Zhang et al. [3] also noted that 60% of ovarian MBT patients presented radiological evidence of lymph node involvement, but after lymph node dissection, the final pathological results showed negative lymph nodes, suggesting a lower likelihood of regional lymphatic spread in ovarian MBT. Therefore, the necessity of lymph node dissection in such diseases remains uncertain.

The role of adjuvant chemotherapy in MBT remains controversial. Gezginç et al. [27]. found that 90% (9/10) of patients receiving the TC regimen achieved complete remission, while 70% (7/10) of advanced-stage patients experienced recurrence after an average of 23.8 months following the aforementioned chemotherapy. Additionally, Yüksel et al. [5] found that all (7/7) patients treated with the platinum-taxane regimen achieved complete remission, with two stage III C patients experiencing recurrence at 86 months and 13 months after chemotherapy, respectively. Therefore, the platinum-taxane regimen as adjuvant chemotherapy demonstrates certain survival advantages post-surgery and may be used as first-line adjuvant chemotherapy for ovarian MBT, despite a high recurrence rate in advanced-stage patients. Regarding radiotherapy, first-line therapy is not recommended. A recent population-based analysis based on SEER reported that 2.4% of MBT patients received radiotherapy during treatment [14]. The postoperative treatment regimen for ovarian squamous cell carcinoma still lacks a unified standard. Based on years of treatment experience and retrospective data studies, most scholars recommend first-line treatment based on a TC regimen [28, 29]; for radiotherapy, some scholars believe that its side effects are significant and unfavorable for prognosis [6]. Through the cases in this study, the TC regimen further demonstrates survival advantages for early-stage MBT patients.

For ovarian MBT, a study based on the SEER database suggested that patients in stages I, II, III, and IV accounted for 55.4%, 14.4%, 18%, and 12.2% of the total number of ovarian MBT patients, respectively. Tumor staging is the most important predictor of disease-specific survival (DSS), with a 5-year DSS of 94.5% for stage I patients, decreasing to 51.3% if ovarian spread occurs [6]. Therefore, early detection and treatment are crucial. Combining the results of this study, Brenner tumors predominantly occur after menopause, with unilateral occurrence being common. The diagnosis of this disease is challenging based on clinical presentation and auxiliary examinations, leading to a certain delay in diagnosis and a certain recurrence rate. There is even a possibility of malignant development after recurrence. Therefore, for postmenopausal patients diagnosed with Brenner tumors, bilateral oophorectomy is recommended where feasible to reduce recurrence and the potential for malignant progression.

Add Comment