First research area: voice description

This section explores the community’s language use in discussing “hearing the voice” and actual instances of voice hearing. Information on onset age, voice count, and characteristics was collected using content-based questions. Open-ended questions further probed these areas and gathered narratives, like first voice-hearing experiences.

DRs of Stabilization are predominantly used by the “External” respondent groups (80%) and “Family and Friends” (65%), at a notably higher frequency compared to the other groups (see Fig. 3). These narratives respond to questions like “how would you describe the voices this person hears?” and generate answers such as “sounds, noises”, “traumas that speak”, or “signs of fate”. These language use modalities are based on personal criteria and absolute responses, and portray AVHs as an unalterable fact. Interactions based on this “narrative style” can potentially lead to stereotyping and, if the contents are semantically negative, stigmatization of AVHs.

In contrast, “Voice Hearers” and “Professionals” groups extensively use Generative DRs (both at 31%). These texts are generated employing recognisable elements, allowing for an AVHs convergence of understanding. Examples include:

-

“One user said that he was in front of the TV and that the people he saw were talking to him, then coming out of the TV and commenting on what he was doing.”

-

“I was going to work in the car and I was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to provide for my new family and the Male Voice told me that I could never make it on my own.”

These two examples show how negative connotations of AVHs can be conveyed in a generative way, i.e. generating a highly shareable scenario. These texts string together various elements in a strictly descriptive logic, free from personal theories or interpretations. The value attributed to the narrative elements is explicit, so that the interlocutor can interact and create a common reality. This way, even with “negative” contents, this DR promotes configurations where all community roles can interact based on the same references, contributing with their perspectives. Thanks to these interactions the motion of the discursive process is increased, countering typification and stigmatization.

Voice onset

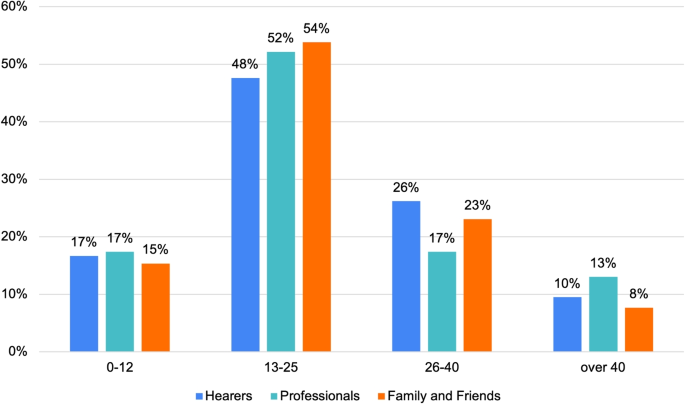

In this section, we examine Voice Onset. Most participants can identify the Voice’s first emergence, namely: 80% of Hearers, 78% of Professionals and 95% of Family and Friends. On this regard, Fig. 4 show a common onset trend within the first 25 years.

Figure 5 provides information on the process-oriented inquiries, finding a high prevalence of Generative DRs among the “Hearers” (59%), generating texts like:

-

“I heard an outside voice as I read Dylan dog saying “you must die”, I went to the cafeteria I took a knife and began to slit my wrists. Then I recovered, as if waking up from a dark world, I went to ask my colleague for help. He called the ambulance and I passed the night in psychiatry”.

Also in this case the discursive modality is characterized by the absence of personal assumptions or values, enabling the interlocutor to engage with the presented scenario and contribute to its development. Additionally, the discourse’s content is transmitted using a logical structure that situates the appearance of voices as one among multiple possible events in the listener’s life story. The language modality employed here is not intended to concretely delineate the manner in which voices emerge; instead, it facilitates an open-ended narrative progression, allowing for a multitude of potential developments, thus contrasting typification and stigma.

Table 2 depicts the results of the processual analysis of the text generated with respect to this dimension. Across different roles, particularly in the “Hearer” group, the emergence of AVHs is experienced as a solitary biographical moment in a private setting. “Professionals” and “Family and Friends” often report negative associations with AVHs’s origin, highlighting the stressful interactions with others and the negative effects of the voice. The answers of these groups allow to observe how AVHs’ insurgence can be conveyed through Stabilization DRs. “I believe it was certainly terrible for her”, for instance, negatively frames AVHs emergence as an absolute reality. These absolutist rhetorics tend to reduce the development of alternative discourses, leading to the stereotypical configuration of AVHs and people experiencing them.

Voice in everyday life

This subsection delves into current voice characteristics, assessing the number and overall sentiment of voices heard. Figure 6a indicates a prevalent negative characterization across research groups. Figure 6b shows a commonality of multiple, sometimes unquantifiable, voices. Figure 7 and Table 3, focusing on process questions, reveals “Hearers” and “Family and Friends” often employ Stabilization DRs with low Dialogic Weight (3.5dW and 3.2dW, respectively). In contrast, the “Professionals” group produced a more generative configuration (4,8dW), positioned mid-way on the continuum. In this regard, content questions revealed a general negative connotation of the voice; however, the process question showed different modes of conveying these contents. This highlights how the same elements can be conveyed through different discursive modalities. For example, the negative connotation of AVHs can be conveyed through DRs like “Judgment” with texts like:

-

“Negative, threatening, offensive, dialoguing, commenting, derogatory voices”.

In the provided examples, the voice’s attributes are framed as an immutable fact. Not explaining the criteria for judging the voices as “negative, threatening, etc.” implies that the underpinning reasons remain implicit and not shared with the interlocutor, who then applies a personal understanding when using these elements. Interactively, thus, through the use of absolute rhetorics and personal criteria, the connotative elements promote stereotyped processes, in which both the hearer and interacting roles continue to perceive the voice’s negativity as a given fact.

The “Professional” group provides useful examples of more generative ways to convey the criticalities of everyday life’s AVHs:

This narrative is constructed on neutral and shareable elements, allowing readers to form a clear image without personal references to fill in the meaning of certain terms. Moreover, the narrative contextualizes the description, presenting elements that could indicate a negative connotation of the voice as aspects of an evolving process. Conveyed in this non-absolutist manner, the contents open up the possibility of “saying something else” about the voice, pragmatically leading to the generation of new discourses on the subject, new directions in the individual’s biographical path, and potentially new management strategies for issues related to the voice.

Second research area: voice implications

This research segment aims to uncover outputs about the effects (present or future) of voice hearing on interpersonal interactions. By combining multiple-choice and open-ended queries, it seeks to explore the integration of voice experiences into participants’ life narratives and the impact on their work, family, and social dynamics. Transversely to the groups, the implications of hearing voices are configured as factual realities.

The text exemplifies how language can exhaust the space for other possible narratives regarding AVHs role in people’s biographical path.

This point is echoed in responses from groups like “Family and Friends”, who, when asked “What do you think are the aspects of a person’s life that are most influenced by hearing voices?”, replied with:

When interactions are based on discursive production like this, typification processes are promoted: voice’s pervasiveness in participants’ lives is seen as a given, hindering the creation of alternative narratives about its value in the daily lives of both the hearer and others involved. Moreover, the absoluteness characterizing these texts frames the criticalities as an element that will continuously be present in the hearer’s life, even in future perspectives.

Figure 8 presents a Likert scale evaluation (1-7) of the voice’s impact on hearers’ lives. Across all groups, a high impact is reported, with most ratings falling between 5 and 7. The Likert evaluation was supplemented by open-ended questions for deeper insight into these scores.

Table 4, examining justifications for these scores, reveals a common theme: respondents generally do not pinpoint specific areas influenced by the voice. The theme “General context of the voice’s influence” appears frequently across all groups, with excerpts like:

-

“[the voice has an impact] when I am stressed, when I have to do something.”

-

“I think [the voices] can affect any aspect and can vary from person to person”

These excerpts also reflect the respondents’ modes of framing the voice’s impact on daily life, mostly falling within the Stabilization DRs. In the examples, the voice’s impact is depicted as pervasive across all aspects of daily life without explicit criteria, keeping the discourse within a personal dimension.

Yet, the data indicate that the influence of the voice on daily life is not uniformly high. Among the “Hearers”, 32% rated the impact as medium or low (4 or below on the Likert scale). Open-ended questions revealed that this variation is marked by the content conveyed, but not necessarily by the modalities. Consider this excerpt:

Here, the voice is framed as a supportive element in daily life. At the same time, the discursive modality employed ties the content’s value to the respondent’s personal criteria, preventing the interlocutor from sharing the value of “they help me a lot in living” and using it towards a common scenario. Thus, even if semantically opposite to community narratives, these discourses limit their potential for changing and interaction the typification and stigmatization processes (Fig. 9).

Third research area: voice management strategies

This section scrutinizes the management strategies for AVHs and their consequences. Content-based queries were utilized to assess the medical management aspect, focusing on psychopharmacological treatments and hospitalization. Subsequently, open-ended questions probed deeper into narrative constructions about medical management, while also inviting descriptions of non-medical management methods (see Table 5). Overall, the discourse predominantly exhibits a stabilization trend (2.35dW). On a semantic level, however, there are opposing positions.

Responses like the ones in the example represent two content-wise opposite examples, yet both frame the scenario as certain and unchangeable. The first scenario implies a definite inability to manage, while the second assumes successful self-management as a fact. These scenarios have potential critical implications (Fig. 10).

In the first (“Inability to Manage”), the manifestation of AVHs is always seen as problematic, with this perception extending into the present, past, and future. This absolutism limits the expression of alternative viewpoints, framing prompts delegation processes, where managing the difficulty is deferred to others, reducing the chance to develop useful management skills.

In the second scenario, since successful management is taken for granted, there’s a lack of anticipation for alternative strategies if usual methods fail. In unforeseen situations where personal resources are insufficient, this could lead to critical outcomes, affecting the biography, like hospitalization.

This last anticipation is of particular relevance since the most frequent theme across roles is “Self-Management”. Similar anticipations can also be applied to excerpts conveying contents related to the management of voices through the interaction with others, such as “Management with a Professional”, “Management with a Psychologist”, or “Listening/Understanding by others”.

Consider this example:

This text presents a scenario where reliance on others is the sole management strategy for the challenges of AVHs. This suggests potential difficulties, especially if such supportive roles are absent, leaving those involved vulnerable to uncertainty and risk. Moreover, even if supportive roles are consistently available, challenging situations may arise that are difficult to manage, leading to critical issues in the biographies of those involved.

Finally, various respondents resorted to Generative DRs, albeit less frequently. The text “Some strategies they often use include writing their thoughts in a notebook, listening to music, or keeping the TV off” delineates self-management techniques for AVHs, offering a detailed perspective and supplying elements conducive to interaction. This approach fosters a collaborative environment, empowering individuals to leverage the provided information as tools in managing voice experiences. These narratives, therefore, not only differ from the community roles’ delegation processes but also offer potentially valuable material for developing new management practices for AVHs.

Hospitalization and psychopharmacological treatment

This section delves into the impact of Auditory Verbal Hallucinations (AVHs) on hospital admissions and psychopharmacological treatment usage. As introduced, these aspects are often seen in the scientific discourse as indicative of AVHs being a psychopathological issue under medical purview.

Figure 11 shows that the “Professionals” and “Family and Friends” groups are more likely to report hospitalizations. In contrast, the “Hearers” group demonstrates a lower tendency for such interventions. These findings challenge the prevalent medical narrative, which typically links the emergence of hallucinations to hospitalization, as Mueser et al. [33] suggest.

Table 6 illustrates a consistent use of psychopathological terminology by all three roles in discussing hospitalization experiences. Notably, as shown in Fig. 12 “Professionals” mainly employ Stabilization and Hybrid DRs, resulting in a lower generative discourse (1.8 dW).

The examples illustrate this: the first phrase sets a certain and absolute scenario, while the second supports it with specific details. The use of these rhetorics hinders the creation of relatable scenarios about hospitalization. For instance, the term value of “severe discomfort” is personal, which could lead to issues in interactions with others, such as hearers or their families, who might not agree with this characterization and oppose hospitalization decisions. Such disagreements could trigger critical consequences like involuntary hospitalization, leading to the development of typification processes.

In contrast, the “Hearers” and “Family and Friends” groups, with 4,7 dW and 3,8 dW respectively, frequently use Generative Discursive Repertories. An example is:

-

“I heard these voices saying my friends were in danger, I went to the emergency room claiming I was a medium and needed to be suppressed, and the psychiatrist admitted me here at the csm.”

In this instance, the content also depicts a scenario leading to hospitalization. However, the used DRs allow for a deeper exploration of the situation, enhancing understanding about the subject, thus creating a different narrative configuration. This configuration of AVHs management fosters the development of inclusive strategies that, by using recognisable and relatable references, recognize and value contributions from a range of roles, promoting their collaborations and countering the emergence of stereotypes or stigma.

Finally, Fig. 13 reveals varying patterns in psychopharmacological use among different roles. While “Professionals” and “Family and Friends” show a clear inclination towards medication use (especially the former), the “Hearer” group is evenly split between users and non-users. A key takeaway from this data, thus, is that psychopharmacological intervention is not an inevitable consequence of AVHs.

Fourth research area: interactions with community roles

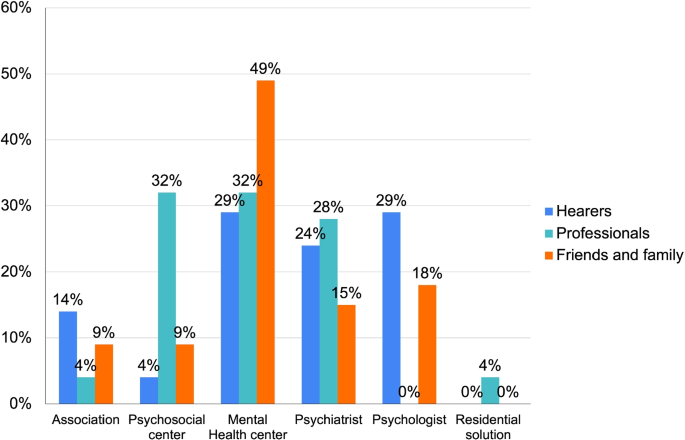

The fourth research area investigates respondent language in defining institutional services’ role in AVHs. Figure 14 indicates “Professionals” and “Family and Friends” predominantly adopt a stabilization discourse approach (see also Table 7).

However, distinct trends are observed for “Hearers” and “External” groups, with the latter heavily relying on Stabilization DRs (87%), leading to a notably low Dialogic Weight of 0.7 dW.

The provided examples illustrate how language is used to define in a general and vague way the roles responsible for managing these implications, based on implicit and personal criteria. This promotes delegation of responsibility to institutional services. At the same time, the modalities through which this management could take shape are not made explicit, creating a fragmentation of medical praxis.

Conversely, the “Hearers” group, despite a general tendency towards stabilization (3,7 dW), exhibited more Generative DRs. Consider this example:

This language use modality, in response to“Why did you turn to the roles you indicated? Explain”, is characteristically descriptive, not relying on personal conceptions or judgments. This way interlocutors are predisposed to engage with the offered content, thereby encouraging the generation of reflections and anticipations based on the presented information. This generative production, in fact, employs discursive processes that assign to the other not a predefined definition, but the role of a legitimate interlocutor for continuing to create a mutually beneficial reality.

Comparing this approach with the responses of the “External” group, it emerges that, while both end in the conclusion of contacting healthcare roles, the manner in which this content is delivered leads to the creation of completely different scenarios and interactive processes.

Using roles to manage critical voice implications

This section examines the interactions with institutional roles in managing AVHs. Analysis of Fig. 15a and b reveals a substantial variation in interactions depending on the request type, especially in crisis scenarios.

Predominantly, respondents in critical situations reached out to local services. Figure 16 further shows these services are mainly healthcare-oriented. Thus, it’s evident that healthcare professionals are often the first point of contact in emergencies, suggesting that delayed intervention could impact the individual’s health outcome.

Table 8 and Fig. 17 reveal that the configurations are predominantly created through Stabilization DRs. Specifically, the most utilized DR is “Certify Reality,” which, in contrast to the explicit theories behind choosing a specific community role, produces statements like:

This extract shows that narratives is closely tied to personal theories and references, which hinder the audience’s engagement with the presented content. This aspect should be considered alongside data indicating that one of the most frequently used topic area relates to “Crisis in Management,” with statements like:

-

“Zero help, zero understanding.”

-

“the psychiatrist didn’t help me at all.”

Hence, on one hand, the relationship with community roles is defined in terms of crisis and as a lack of efficacy; on the other hand, the narrative about unmet needs or requests unfold in personal ways. These last, being strongly related to personal references, impede the initiation of processes that could change the management of these crises, further reducing the effectiveness of these services.

The group of “Hearers” is highlighted for often using Generative DR (25%). Consider the statement:

Here, the engagement with the Association and the reasons for embarking on this path are presented in a more relatable logic. The narrative is characterized by providing the audience with relatable elements that enable them to engage with the presented scenario.

Free from personal judgments or values, this narrative allows participants to use it as a “common convergence element,” initiating new interactions with contributions from all parties involved. Due to the neutrality of the described criterion, the generated text has the potential to be used, for instance, to share objectives with the audience, thus creating a common horizon to which both the community service (role) and the audience can turn together to structure support (such as the development of the competencies that sparked curiosity).

Not using roles to manage critical voice implications

Table 9 and Fig. 18 reveal how both “Professionals” and “Family & Friends” predominantly use Stabilization DRs, resulting in low dW discursive configurations (2.7 dW and 2.2 dW respectively). In this sense the reasons for “not turning to community roles” are framed in terms of certainty.

The example illustrates a “closed” scenario where sedation is viewed as a certain outcome, leaving no room for the anticipations of other results after interacting with community roles. The use of this language modality limits the narrative trajectory a person can create: it pre-defines potential discourses about and from the listener in present and anticipatory terms.

Interactively, this has critical repercussions not just for those who might miss out on support options, but also for the roles responsible for providing these services. They might have to manage these personal beliefs presented by different users. Regarding the role of “Hearers,” they tend to use generative modes more frequently to convey reasons for not engaging with community roles. Consider the example:

-

“I can’t afford it economically, and I’m afraid of finding out that I would need to be helped with psychotropic drugs, therapies, or even confinement.”

This language use modality is based on common criteria, enabling the audience to engage with the content and propose potential strategies for managing these critical aspects. By using these DRs, in fact, interlocutors can position themselves as active community members, thus contributing to the management process of voice-related implications. This example shows how critical issues can be conveyed for generative use: not to maintain the status quo, but as a starting point for creating an alternative reality, thereby countering stereotypes and stigma.

Add Comment