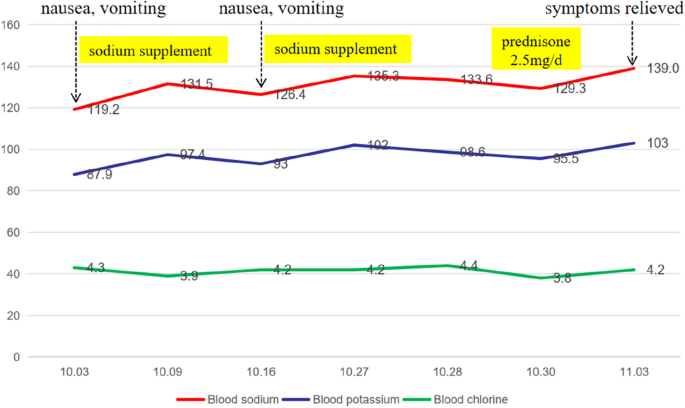

A 55-year-old man presented to our department with fatigue for 2 years, repeated nausea, and poor appetite for more than 20 days. Two years before his visit to our hospital (November 2021), he had contact with a dead mouse and was diagnosed with HFRS (confirmed with positive IgG and IgM antibodies against epidemic hemorrhagic fever virus) after hospitalization (December 21, 2021). During the examination, his urinary protein was 3 + , his serum urea was 15.9 mmol/L↑ (reference range 3.1–8.0), and his creatinine was 612.2 µmol/L↑ (reference range 57.0–97.0). After hemodialysis and systemic treatment, he was discharged with improvement. However, ever since, the patient had felt sluggish all the time and had less appetite than before, without palpitation, sweating or other symptoms. However, he did not pay much attention to this because he thought it was the after-effects of HFRS. More than 20 days ago, the patient developed nausea, vomiting, poor appetite, dizziness, and fatigue without obvious inducement. After being hospitalized at a local hospital, his blood sodium concentration was 119.2 mmol/L, and he was given supplemental sodium and drugs to inhibit gastric acid secretion (reported by the patient). After treatment, his blood sodium concentration recovered to 131.5 mmol/L, and nausea and vomiting eased, but his appetite was still poor. Then, he was discharged. Approximately 1 week later, nausea and vomiting occurred again, and his blood sodium concentration fell to 126.4 mmol/L again. After sodium supplementation, his blood sodium concentration was restored to 135.3 mmol/L in the outpatient department (reported by the patient). Throughout the course of his illness, his weight gradually dropped by about 3 kg over two years, and he had no other symptoms, such as cold intolerance or loss of libido. For further treatment, he was hospitalized in our department.

On physical examination, he presented with normal vital signs (Body temperature 36.5 °C, Pulse 67 beats/min, Respiration 19 breaths/min, Blood pressure 140/90 mmHg), and his weight, height, and body mass index were 56 kg, 164 cm, and 21 kg/m2, respectively, with no obvious abnormalities in the eyebrows, pubic hair, or armpit hair or no other positive signs.

According to the auxiliary examination, his routine blood test was normal (eosinophils 0.13 × 10^9/L [reference range 0.02–0.52]), renal function was normal (urea 3.9 mmol/L [reference range 3.1–8.0], blood creatinine 90.5 μmol/L [reference range 57.0–97.0]), and his urine specific gravity was 1.017, without any significant anomalies in other examinations, such as routine stool tests, liver function tests, blood lipids, fasting blood glucose, cardiac troponin, brain natriuretic peptide, tumor markers, or hemoglobin A1c. The 24-h urine output during hospitalization was 1280 to 2670 ml. When the patient’s blood sodium concentration was 133.6 mmol/L, his urine sodium concentration was 73.4 mmol/L, and the changes in serum electrolytes are shown in Fig. 1.

He had no signs of hypothyroidism or hypogonadism. Consistently, his blood levels of thyroxine (TSH 6.050 mIU/L 0.35–5.1, FT3 3.43 pmol/L 2.76–6.45, FT4 5.91 pmol/L 11.2–23.81), testosterone (2.08 ng/ml 1.75–7.81), growth hormone (GH, 1.25 µg/L 0–2), prolactin (7.91 µg/L 2.64–13.13), luteinizing hormone (4.44 IU/L 1.24–8.62), and follicle stimulating hormone (6.16 IU/L 1.27–19.26) were all normal. However, both the plasma cortisol and the 24-h urinary-free cortisol were somewhat low, with plasma cortisol of 4.84–5.67 µg/dl at 8 AM and 24-h urinary-free cortisol of 22.8 µg (reference range 50–437 µg/24 h), and insulin tolerance test (ITT) showed no response of cortisol (peak cortisol level was 5.86 pg/ml) (As shown in Tables 1 and 2).

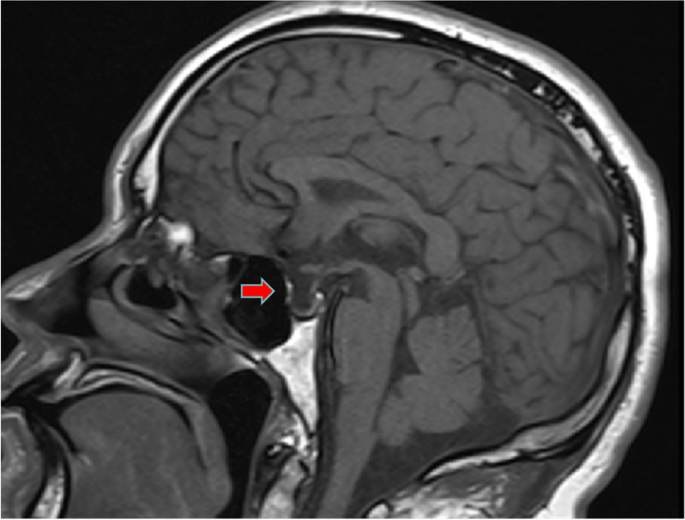

Similarly, enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary showed an empty sella (Fig. 2). A CT scan of the adrenal gland and electrocardiogram showed no obvious abnormalities. Gastroscopy suggested erosive gastritis. Chest and abdominal CT showed scattered intrahepatic cysts or hemangiomas.

Diagnosis and treatment process

The patient had no history of special diseases or drug use, and no significant abnormalities were found via gastroscopy, tumor marker analysis or chest or abdominal CT examinations after admission. After excluding other potent causes of nausea, such as drug sources, physical disease, potential malignant tumors, and nervous system disease, the patient was considered to have hyponatremia because his symptoms could partially recover with the recovery of hyponatremia.

The patient was diagnosed with central adrenocortical hypofunction after excluding hypertonic hyponatremia, insufficient sodium intake due to digestive tract diseases, digestive tract loss, brain salt consumption syndrome, increased extracellular fluid, antidiuretic hormone secretion disorder syndrome, hypothyroidism and other diseases that may lead to hyponatremia. His blood sodium concentration was 133.6 mmol/L, his urine sodium concentration was 73.4 mmol/L, his serum cortisol concentration was low many times, and his ACTH concentration was improperly at a normal level. Moreover, there was no response of cortisol in the ITT (for a peak cortisol level of 5.46 pg/ml). In addition, pituitary MRI indicated a vacuolar sella that also supported central adrenocortical hypofunction. This patient’s testosterone, growth hormone, prolactin, luteinizing hormone, or follicle stimulating hormone were normal. He had a mildly elevated TSH level and decreased FT4 level, but he had less appetite for the past 2 years, repeated nausea for more than 20 days, and didn’t had any symptoms associated with hypothyroidism. In addiction, his testosterone, prolactin, luteinizing hormon, and follicle stimulating hormone were all normal. Thus, insufficient T4 reserve due to insufficient iodine intake might mainly contribute to his abnormal thyroid function, which might be confirmed by further follow-up. Therefore, he was considered to have isolated ACTH deficiency at first. After admission, 2.5 mg of prednisone was administered orally at 8 AM daily. Three days later, his blood sodium concentration recovered to 139 mmol/L, his fatigue and appetite loss were completely relieved, and his spirits were good. Five months later, his thyroid function did improve (TSH 5.24 mIU/L 0.35–5.1, FT3 3.69 pmol/L 2.76–6.45, FT4 10.4 pmol/L 11.2–23.81), but TSH level was still mildly elevated and FT4 level was decreased. Meanwhile, the measurements of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) were supplemented for him, and they were both decreased (IGFBP-3 3.02 µg/ml, reference range 3.5–6.7; IGF-1 49.72 ng/ml, reference range 87–234). Thus, he was finally diagnosed as partial hypopituitarism (ACTH deficiency, TSH deficiency, and GH deficiency). Since he was in excellent health, thyroid hormone and growth hormone were not supplemented for him.

Add Comment