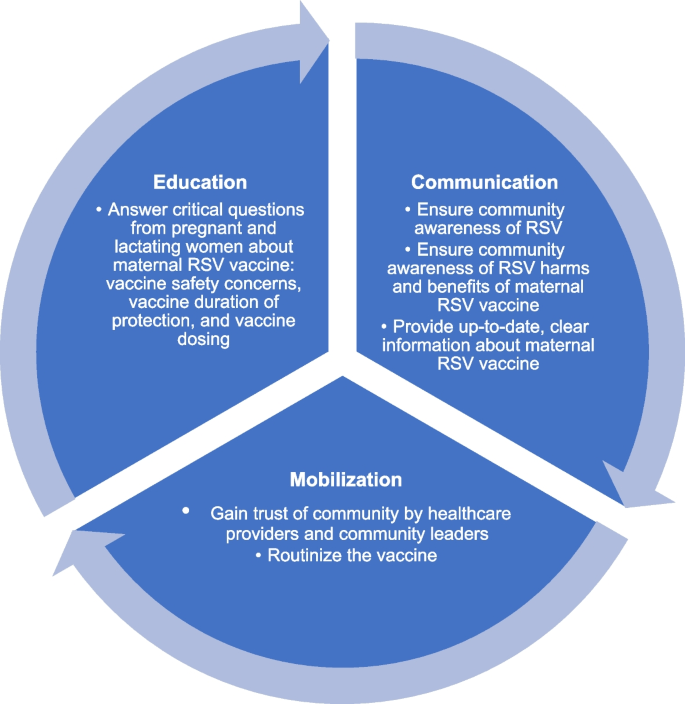

A total of 16 healthcare providers were interviewed. No minors or lower-literate individuals were involved in the study.Given that COVID-19 vaccine rollout was occurring during the time of data collection, including among pregnant and lactating persons in Kenya, healthcare providers provided lessons learned from the COVID-19 vaccine experience rollout to inform future maternal RSV vaccine rollout. The most prevalent lesson that emerged was related to community sensitization broadly, including communication, mobilization, and education specifically. While communication, mobilization, and education can overlap, we sought to articulate each domain based on the results (Fig. 1). For communication, participants identified using communication to ensure community awareness of RSV disease, of the potential harms and benefits of RSV maternal vaccines, and provide up-to-date, clear information about maternal RSV vaccines. Related to mobilization, participants identified the need for healthcare providers and community leaders to gain the trust of community members and making the vaccine a routine part of prenatal care. Finally, for education, participants outlined critical questions that should be answered which included vaccine safety concerns, duration of protection, and vaccine dosing.

Community sensitization regarding future maternal RSV vaccines: communication and mobilization

Healthcare providers stressed the need for communities to know about RSV disease generally, as articulated by this healthcare provider from Nakuru: “The communities need to understand first. What is this RSV? Just basic knowledge. Then you will need to explain to them that the cough you’ve been having, the chest pains, is this virus and we are intending to give you a vaccine to prevent all these problems. They need to understand why and what is this RSV first.” (Kamara Dispensary, Nakuru). In addition to basic awareness about RSV disease, this healthcare provider from Mombasa believed that RSV vaccine acceptance would be easier if the community was able to see the harms of RSV as well as the benefits of a maternal RSV vaccine. This was because the community was able to see the negative effects of COVID-19 disease and the positive benefits of the vaccine: “With the lessons learnt with COVID-19—and the fact that the RSV vaccine is coming post-COVID, I think it will be an easier time for community to embrace an RSV vaccine because we saw how COVID killed people and this is another disease affecting the respiratory trachea—this gives the seriousness of the vaccine to the people. The healthcare workers (will accept an RSV vaccine) because this is a disease that is affecting our breathing system and this is another disease like COVID which was very serious—as it was killing people in masses. I’m seeing that in the future the RSV vaccine being more acceptable than the other previous vaccines that were introduced, provided that people will know the benefits, what the disease is, and if taking the vaccine, will it completely give proper immunity from this disease.” (Tudor Sub-County Hospital, Mombasa). Additionally, this point about whether a new vaccine would ‘give proper immunity’, i.e., prevent infection of the disease also points to the importance of communication and education about what the vaccine can do to manage expectations.

In addition to understanding the harms and vaccine benefits, clear information about the safety of the vaccine was crucial for COVID-19 vaccine uptake among pregnant and lactating people. As such, healthcare providers suggested ensuring that there was up to date and accurate information related to the safety of maternal RSV vaccines. Accurate information was of particular importance for successful uptake, as this healthcare provider relayed how safety of the COVID-19 vaccine changed over time, and how this affected attitudes and uptake among pregnant and lactating women: “Now, one thing I remember when we started rolling out this COVID vaccination to everyone, the first… there was information that was available that said it is not safe to pregnant women. That information actually affected everything. So pregnant women seeking the vaccine were very low. Actually I remember teachers were prioritized for the vaccine, and pregnant teachers did not take the vaccine. Because the information was that it is not safe for them. I think the information that is available guides us and guides the pregnant women seeking that vaccine. So if this new RSV vaccine will come with information that it is safe in pregnancy, I think pregnant women will take it. There are still those pregnant women that are resistant.” (Kiptangwanyi Health Centre, Nakuru). This healthcare provider from Mombasa still perceived resistance to COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women in the community they served: “The community has not embraced the COVID vaccine in pregnant mothers. The reason is that there are misconceptions which are around, and so the community has not embraced COVID vaccines. The community—they have not accepted that this vaccine is safe because they still believe the vaccine has not been tried well and so the pregnant mothers are hesitant even now.” (Mlaleo Health Centre, Mombasa). This healthcare provider from Mombasa reflected upon the need for wide dissemination of information related to vaccine safety to communities given the COVID-19 experience: “For now, I can say that there are fewer concerns about COVID vaccines compared to the first time that they introduced this vaccine. The first time—that’s when rumors were going that the vaccine should not be given to pregnant women. But now, people have enough knowledge, we have seen a lot of women here after you have finished with their appointment they ask for the covid vaccine, they ask where can I get my booster. And now because the first people were lacking that knowledge about the vaccine but now everyone is enlightened about it and they are ready to go and take the vaccine.” (Naivasha Sub-County Hospital, Nakuru). This healthcare provider articulated how healthcare providers themselves first believed that the COVID-19 vaccine was unsafe, but this concern was allayed over time with up-to-date accurate information, and how community word-of-mouth was so powerful for acceptance: “Initially there was that worry even among the healthcare workers that the COVID vaccine was unsafe, but when they provided information about its safety and people were educated about it, and were told that now it is safe, actually at the community level, I had people calling when they are pregnant, that they now want vaccination. One community member can spread word to so many.” (Tudor Sub-County Hospital, Mombasa). Given the concerns among healthcare providers, this healthcare provider from Mombasa pointed to the importance of healthcare providers being sensitized first with the most complete information, so that they could subsequently recommend a new vaccine to their communities: “If recommended by the MOH, that means that they have consulted WHO and it is safe for our mothers, so I think I would recommend that the community to be aware of it. But us healthcare workers should be first to be sensitized on the RSV vaccine, and know about it, meaning knowing the benefit, what it is, how is it given, what is the dose, how many doses, where it is given.” (Tudor Sub-County Hospital, Mombasa).

This healthcare provider from Nakuru asserted the importance of patience and identified building trust as critical for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: “It was not easy to persuade pregnant women to get the COVID vaccine, it wasn’t easy. We had to do a lot of health education, inform them more on the risks, talk to them when they come for the first visit. Even if they first do not accept, just continue, have the patience, talk to them, talk and talk, it took so much, it was not easy. But finally, they accepted. But if one accepts, you have already won. They were really afraid that they could miscarry, or have babies without limbs and such things. But when we managed to vaccinate one, she became a champion. Slowly trust was built. So now at least they have the knowledge and ask for it.” (Kamara Dispensary, Nakuru). Trust was also the reason why community members sometimes listened to community leaders over healthcare providers in the community this healthcare provider from Mombasa worked in: “My role is very crucial for new vaccine uptake like RSV, especially to the community to accept and having had the experience of doing several campaigns on vaccinations of polio vaccine, tetanus vaccine, the community has its own perceptions especially when it comes to vaccines. We did a campaign on tetanus but the turnout was very low because the community listens to and trusts its leaders more than the healthcare workers.” (Tudor Sub-County Hospital, Mombasa).

Finally, healthcare providers alluded to including any new vaccine in the routine vaccine schedule for successful acceptance, including future maternal RSV vaccines. This healthcare provider from Mombasa referenced the routinization of tetanus vaccination during pregnancy as an essential factor for maternal tetanus vaccine acceptance and as an important lesson for future maternal vaccine acceptance: “Pregnant women were able to come for the normal tetanus vaccination. It was simple because it was a normal routine vaccine, and the pregnant women already were given information and the importance of it. That is why they were not reluctant about accepting it.” (Port Reitz Sub-County Hospital, Mombasa). This healthcare provider from Nakuru also referenced routinization of vaccines, and how a vaccine for pregnant women specifically will be easier for pregnant women to accept, in comparison to COVID-19 vaccines: “You know COVID was for everybody but if you introduce a vaccine for the… mothers only—that one is different. Because when pregnant women come to the facility we tell them there is a new vaccine for this specific disease, and we are giving it to you at this gestation period. They will have no option but to accept it. But COVID was different because it was for everybody.” (Bahati Rural Health Centre, Nakuru).

Community sensitization regarding future maternal RSV vaccines: education to answer questions about future maternal RSV vaccines

Healthcare providers identified vaccine safety as the primary concern pregnant and lactating women would have about a maternal RSV vaccine. These concerns included how the vaccine could potentially affect the unborn child, infant, and mother. Per this healthcare provider from Nakuru: “The pregnant women will first be worried about the potential side effects from the vaccine, and the lactating mothers—almost all of them will ask if it will affect the child, and will it affect breastfeeding. Maybe some will say that when you take a certain vaccine that there is that reduction of breast milk. So I think they would ask those questions.” (Naivasha Sub-County Hospital, Nakuru). This healthcare provider from Mombasa had similar feedback: “Women will ask—does (the RSV vaccine) have teratogenic effects which could affect my child negatively? Those pregnant mothers will ask, is it going to make me sick? Because most of those immunizations give low grade fevers, the malaise and the chills. Will the RSV vaccine have those side effects? Or the breastfeeding mothers, they have those worries of leaking through the breast to the child, they will ask—is it going to affect my child negatively or positively? Those are the big worries.” (Likoni Sub-County Hospital, Mombasa). Besides these concerns, healthcare providers also raised the potential effects of the vaccine on breastmilk, per this healthcare provider from Nakuru: “The pregnant women will first be worried about the potential side effects from the vaccine, and the lactating mothers—almost all of them will ask will it affect the child, will it affect breastfeeding. Some will say that when you take a certain vaccine that there is that reduction of breast milk. So I think they would ask those questions about this new vaccine.” (Naivasha Sub-County Hospital, Nakuru).

Additional questions healthcare providers thought pregnant and lactating people would raise were related to duration of protection, dosing, and why the pregnant woman was being targeted for vaccination, as illustrated by this healthcare provider from Mombasa: “Is it a lifelong, how long, is it lifelong, once you get it once, with subsequent pregnancies, will I still need to get the vaccine? How will I benefit from the RSV vaccine and how about my husband and the other children or the other family members, why is it only me getting the vaccine?” (Tudor Sub-County Hospital, Mombasa). This healthcare provider from Mombasa also raised dosing: “Is it a repeated vaccine or is it a single vaccine—what is the dosage?” (Miritini Health Centre, Mombasa).

Add Comment