GP sample

Fifty-two GPs completed the baseline survey including sociodemographic information (see Table 1). A majority of 61.5% of GPs identified as female, with 71.2% located in urban Victoria with a mean age of 48.1. Over 80% of GP had completed their medical education in Australia. Previous IPA training varied, with 53.3% having completed two or less hours of training with only 15.6% having completed over six hours of IPA training. Less than half (42.9%) of the GPs had undertaken mental health training.

Survey

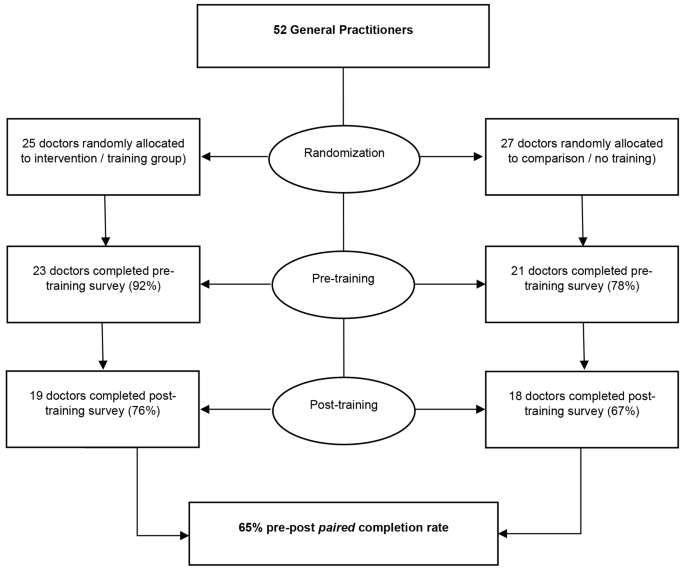

Whilst 52 GPs completed baseline survey, 65% (n = 34/52) completed all pre-and post-training surveys (see Fig. 1). There were no between-group differences in baseline characteristics (see Table 1). Whilst no statistically significant group differences were seen, there was a pattern that urban-based and female GPs were slightly over-represented in this sample [7].

Means and standard deviations for the PREMIS domains are presented in Table 2 for pre-and-post-training for both intervention and comparisons groups. Results indicate that post-training, the intervention group had higher mean scores on perceived and actual IPA knowledge(see Table 2). This means the intervention groups perceived knowledge, what they felt they knew about IPA identification and management and their actual knowledge about IPA identification and management, increased. See Additional file 1 for more information on perceived and actual knowledge measures. The repeated measures MANOVA, with time as the within-subjects variable, revealed a significant difference in perceived knowledge between intervention and comparison group (F(1,32) = 19.56, p < .001, partial eta squared = 0.379). In comparison to the control group, the intervention group showed higher average scores on perceived preparation to address IPA (F (1,30) = 16.01, p = .000, partial n2 = 0.348), perceived IPA knowledge (F (1,32) = 19.56, p = .000, partial n2 = 0.379), actual IPA knowledge (F (1,32) = 5.15, p = .030, partial n2 = 0.139), and greater awareness of practice issues (F (1,32) = 10.51, p = .003, partial n2 = 0.247). Results detected no between group difference in PREMIS opinion domain scores of preparation, workforce issues, self-efficacy, alcohol and other drugs, and victim understanding. Both intervention and comparison groups had similar pre-post training scores across these domains (see Table 2).

Open-text responses

Twenty-four (96%) GPs in the intervention group contributed to open-text responses in the three surveys. Four themes were identified post training from the intervention group: (1) increased knowledge and awareness of IPA, (2) GPs gained confidence in identifying and responding to IPA, (3) time pressures impacting on GPs perceived self-efficacy and (4) available referral pathways to support GPs and patients.

Increased GPs’ knowledge and awareness of IPA

In the baseline and pre-training surveys, an overwhelming majority of respondents in the intervention group (91.7%) reported a lack of knowledge, skills, and awareness of IPA in their patient population.

‘This is an area I feel I do badly at and need further knowledge.’ – Male, Urban GPs (intervention group, pre-training survey #3).

‘[I want to] Improve knowledge re: specific psychological issues and evidence of what works when helping women and improved knowledge re: referral options.’ – Female, Urban GP (intervention group, pre-training survey #4).

Post-training surveys reported an increase in IPA knowledge and awareness which was noted in the intervention group responses. These respondents acknowledged that a patient’s readiness to change may vary, and ongoing support and validation of experience was essential.

‘[I am] more aware of the very long-term damage from being in an abusive relationship – some of the women I counselled had been out of the relationship for many years, but it was still having a very major impact on their lives.’ – Female, Urban GP (intervention group, post-training survey #4).

‘To realise how much I had failed to recognise the extent and nature of the problem and to correct the habit of doing so; to correct my tendency to attribute blame to the victim for apparent provocation and failure to leave’ – Male, Rural GP (intervention group, post-training survey #14).

GPs gained confidence in identifying and responding to IPA

In the baseline and pre-training surveys, intervention GPs (n = 16) noted that they were not confident in asking about IPA and how to support patients if they disclosed IPA.

‘Not knowing who/ how to ask’ – Female, Rural GP (intervention group, baseline survey #21).

‘Lack of confidence in knowing what to do once they disclose.’ – Female, Rural GP (intervention group, pre-training survey #38).

‘…GP having the interest and time to spend with her and the knowledge to discuss safety issues after assessing her risk of being harmed by her partner’ – Female, Rural GP (intervention group, pre-training survey #38).

However, in post-training surveys collected after the training, intervention GPs self-reported an increase in confidence, a greater understanding of the impact of IPA on victim-survivors, and an improved ability to facilitate discussions about IPA and establish patient safety.

‘[I gained] more confidence in asking about IPA, increased awareness of the possibility of IPA, more understanding of the effects of IPA, more confidence in being able to assist women experiencing IPA.’ – Female, Rural GP (intervention group, post-training survey #38).

‘[I am now] comfortable asking sensitive questions. Will ask more. Assessing risk.’ – Female, Urban GP (intervention group, post-training survey #17).

Time pressures with IPA patients impacted GP’s self-efficacy

In either the baseline or post-training survey, over half of the GPs (n = 16) in the intervention group mentioned time pressures limiting their ability to address IPA. Survivors often required lengthier consultations, longer than that for which GPs perceive they are poorly remunerated for, which impacted on their willingness to discuss IPA with patients.

‘Poor remuneration for prolonged consultations’ – Female, Urban GP (intervention group, baseline survey #37).

‘Time, time, time. I wish I can have more time talking to the patients to find out their real problems and to help them. – Female, Urban GP (intervention group, baseline survey #41).

‘Time may be a factor, but a longer consult can be arranged.’ – Male, Urban GP (intervention group, baseline survey #49).

Post-training survey’s respondents in the intervention group varied in their ability to manage the time pressures and the psychological impact of clinically supporting IPA patients, with some intervention GPs able to prioritise patients experiencing IPA, while others found it personally more challenging even after training.

‘I do find it stressful asking about the possibility of IPA as it takes time and sensitivity dealing with a positive response’ – Female, Rural GP (intervention group, post-training survey #38).

‘It takes more effort and is likely to put me more behind, so I do sometimes consciously make the decision not to ask about possible IPA, which I don’t feel good about’. – Female, Rural GP (intervention group, post-training survey #38).

Available referral pathways supported GPs and their patients

In the post-training survey, intervention GPs (n = 21) reported that access to community resources and referral services enabled them to effectively support patients experiencing IPA.

‘Rapid access to affordable help and advice… Good knowledge of how to access other services.’ – Female, Urban GP (intervention group, post-training survey #4).

The training was able to increase intervention GPs’ knowledge of local resources available.

‘Increased understanding, knowledge, and skills and tools for assessing and supporting women with current or previous IPA.’ – Female, Rural GP, (intervention group, post-training survey #46)

‘[I have gained] greater knowledge of community resources.’ – Male, Urban GP (intervention group, post-training survey #5).

Add Comment