The LIKE programme

LIKE is part of the Amsterdam Healthy Weight Programme (AHWP), a local-government-led whole systems approach with the long-term goal of reducing childhood overweight and obesity in Amsterdam, the Netherlands [16]. LIKE focuses on the transition from child to adolescent (ages 10–14) and is implemented in three ethnically diverse neighbourhoods with a lower socioeconomic position in the Amsterdam East district. LIKE uses a SD and participatory action research approach in developing, implementing and evaluating a dynamic action programme that can help change the current system towards one where healthy lifestyle behaviours are promoted [17]. The LIKE consortium is a transdisciplinary team consisting of academic researchers, policymakers at the city level and Amsterdam East district and professionals working for the AHWP.

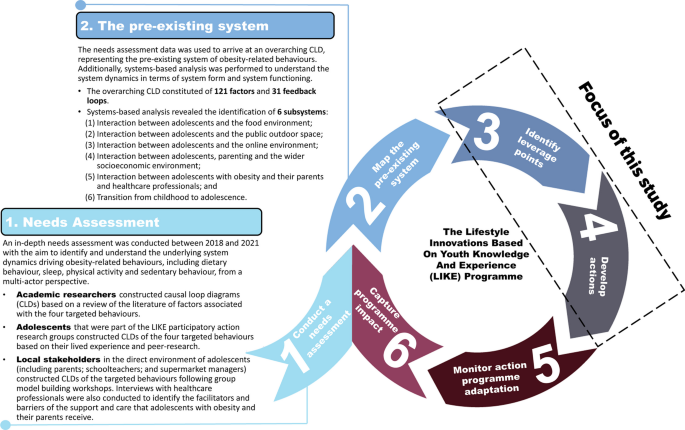

The LIKE programme centres around a six-stage cyclic process, including: (1) conduct a needs assessment; (2) map the pre-existing system; (3) identify LPs; (4) develop actions; (5) monitor action programme adaptation; and (6) capture programme impact (Fig. 1) [3]. Stages 1 and 2 took place between 2018 and 2021 and involved an in-depth mixed-methods needs assessment [17, 18]. This needs assessment captured an understanding of the underlying SD driving obesity-related behaviours from the perspective of multiple actors, including academic researchers, adolescents and local stakeholders, into a CLD. This CLD contained 121 factors and 31 feedback loops and consisted of six subsystems, including: (S1) interaction between adolescents and the food environment; (S2) interaction between adolescents and the public outdoor space; (S3) interaction between adolescents and the online environment; (S4) interaction between adolescents, parenting and the wider socioeconomic environment; (S5) interaction between adolescents with obesity and their parents and healthcare professionals; and (S6) transition from childhood to adolescence [15].

The current study builds on these system insights to develop a participatory SD action programme by identifying LPs (stage 3) that inform the development of actions (stage 4). In LIKE, adolescents and local stakeholders developed various action ideas using participatory action research (Emke et al., in preparation, 2024) and GMB (Waterlander et al., in preparation, 2024), respectively. In parallel, the LIKE consortium initiated additional action ideas by building on the insights gained from the action development process by adolescents and local stakeholders; targeting the functioning of the system; and conducting systems-based analysis. These consortium-initiated actions are the focus of the present paper.

Both stage 5 (monitor action programme adaptation) and stage 6 (capture programme impact) will be addressed elsewhere (de Pooter et al., in preparation, 2024; Luna Pinzon et al., in preparation, 2024). Furthermore, the current paper will not assess implementation, outputs and outcomes of the action programme. The remaining part of the methods section illustrates how the LIKE evaluation team (WW, ALP, NdP, KS) guided the LIKE consortium through a series of steps to identify LPs and develop action ideas. This study was approved by the institutional medical ethics committee of Amsterdam UMC, Location VUMC (2018.234).

Procedure for the identification of leverage points and development of action ideas

The evaluation team guided the LIKE consortium through six steps to identify LPs and subsequently develop action ideas. These steps are outlined below in more detail.

Step 1: identifying underlying mechanisms

Step 1 involved determining which SD within the pre-existing system the LIKE consortium aimed to target (first). In February 2020, the LIKE consortium discussed all the collected data as part of the needs assessment stage thus far, focusing on the produced CLDs supplemented with data from the participatory action research groups and an overview of actions already taking place in the Amsterdam East district. All this information was collectively discussed with the aim to identify and prioritize underlying mechanisms, that is, a segment of a larger process in the system (causes of the causes) [18, 19], by asking the question: Taking into account the needs assessment results, what are the most important mechanisms contributing to unhealthy lifestyles among adolescents aged 10–14? Mechanisms were prioritized by considering system boundaries, which define the system parts that are included or excluded for this particular analysis [3]. These boundaries related to, for example, the focus on the transition period from childhood to adolescence and Amsterdam East as the setting.

Step 2: action-groups formation

In step 2, the LIKE consortium split up into groups to work on the identified mechanisms. Participants could join one or multiple groups on the basis of their expertise and/or interest. This resulted in the formation of five action-groups. A prerequisite was for each group to include at least two academic researchers, one professional working for the AHWP and one policymaker working for the municipality. Action-groups were encouraged to meet regularly to discuss their plan of action and plenary meetings with all action-groups were organized by the evaluation team every 6 weeks to discuss progress.

Step 3: further refinement of the identified mechanisms

In step 3, the evaluation team guided action-groups in understanding the targeted mechanisms from an SD perspective. Each group received an action-group workbook [see Additional file 1] with different sections to complete. These sections included: a description of the mechanism based on academic literature; an assessment of why the mechanism was relevant to the transition from child to adolescent; and an assessment about why the mechanism was particularly relevant at this moment (in comparison with, for example, 20 years ago). Action-groups were also encouraged to consult external experts to further refine their mechanisms.

Step 4: identification of leverage points and system levels analysis

Step 4 aimed to identify LPs that would help disrupt the identified mechanisms. To achieve this, we conducted systems-level analysis by applying the Intervention Level Framework (ILF). The ILF was developed by Johnston and colleagues to assist in finding solutions to complex health problems [13]. The ILF consists of five system levels and intervening at the higher levels will produce the most disruptive systems changes. The highest ILF level is a system’s paradigm, representing its deepest-held belief. Level two, the system, together with the system paradigm, dictates the way in which the system behaves and determines which system outcomes are produced. Level three is the system structure and defines the interconnections between the different system parts. Level four describes the system’s feedback and delays. This level refers to a system’s ability for self-regulation by supplying information about outcomes of actions back to the source of those actions. Lastly, level five describes the structural elements of a system in terms of actors or physical elements [13].

The action-groups used a table explaining the ILF levels and conducted ILF analysis. This analysis involved the identification of LPs for their mechanisms and the assignment of one of the five ILF levels to each LP. To facilitate this, action-groups used guiding questions, such as those described in the Action Scales Model [14]. For example, the following question helped in identifying a LP at the system paradigm level: What are the prevailing assumptions, beliefs and values that explain why things are done as they are? [14] LPs and their corresponding ILF levels were included in the action-group’s workbook [see Additional file 1].

Step 5: generating action ideas

In step five, action-groups generated action ideas on the basis of the identified LPs. At the action idea level, it was important for groups not to focus on the specific form of the action (e.g. a workshop) but to specify a theory of change in terms of the action function [3]. In other words, the theory of change specified how the particular action would target the identified LP, thereby contributing to disrupting the targeted mechanism and thus ultimately aiding in achieving the desired systems changes. To facilitate this, action-groups answered the question: Which actions can help target the LP and ultimately aid in achieving systems changes (define action idea in terms of action function and using the S.M.A.R.T criteria [20])? Action ideas were added to the action-group’s workbook [see Additional file 1] and included these characteristics: targeted mechanism and LP, system level (ILF level), action name, action form and action theory of change.

Step 6: assessing the degree to which action ideas could be embedded in existing initiatives

In step six, action-groups investigated which actions were already happening in the LIKE focus area to determine the degree to which action ideas could be embedded in existing initiatives. Action-group members working for the AHWP and municipality provided this information. Lastly, action-groups were encouraged to involve external stakeholders to aid in the further development of the action ideas.

Reflection, adaptation and monitoring

Action development continuously occurred in a cyclic process, wherein ideas were adapted on the basis of the context and setting in which they ought to be implemented, as well as the feedback received from the evaluation team. For example, during action development, if it became apparent that an action idea was not feasible due to a lack of alignment with existing initiatives or redundancy, the idea was either adapted or abandoned. Similarly, efforts to emphasize actions at specific system levels were adjusted over time. For instance, the focus on targeting higher system levels was increased when we observed a shortage of action ideas at those levels. The evaluation team supported action-groups in applying systems thinking throughout the action programme development process via developed workbooks (see Additional file 1), the use of guiding questions and by organizing plenary meetings. To track the progress of the action programme, a monitoring system was set up, composed of: action-group’s workbooks; action register database containing, for example, name, action form and function; and stakeholder database containing the type of stakeholders involved.

Data sources and analysis

For data analysis, the lead researcher (ALP) read and summarized all action-group workbooks and extracted action ideas generated by the LIKE consortium from the action register database. A second researcher (NdP) supported this process. Note that action-groups generated various action ideas throughout the process, and that not all actions were actually executed or specified into detailed action plans. This paper focuses on all actions for which action-groups provided specified theories of change. Identified mechanisms, targeted LPs and corresponding action ideas were ordered per subsystem. The evaluation team discussed preliminary findings to ensure that these reflected the process followed within the LIKE programme.

Add Comment