The study targeted 193 mother-child dyads; however, 189 mother-child dyads were accessible (response rate: 97.9%). Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of the sampled participant’s households. The mean maternal age was 27.68 years (± 6.40 SD). The age of the mothers varied from 18 to 44 years whereby a majority; 88 (46.6%) belonged to the age category of 18 to 24 years. In terms of marital status, a majority; 158 (83.6%) of the participants were married and slightly more than average; 106 (56.1%) were of Pentecostal religion. Almost three-quarters; 133 (70.4%) of the participants were drawn from households comprising of 3 to 6 household members with the mean household size being 5.63 (± 1.86 SD). Almost all the participants; 179 (94.7%) reported that the mother was not the head of the household. Slightly more than half; 102 (54.0%) of the children were female. Furthermore, the study found that the mean age in years for the children was 1.94 (± 0.64 SD). More than three-quarters, 150 (77.7%) of the participants reported that they had completed primary school level of education.

Table 2 displays the profile of participants recruited for the Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs). For the male FGDs, all (100%) reported to have completed secondary school level of education. A high proportion, 4 (57.1%) of them were aged 45 to 49 years. For the female FGDs, more than half, 3 (60.0%) reported to have completed secondary schools level of education and most of them, 4 (80%) were aged 40 to 45 years. For the KIIs, a high percentage, 4 (66.7%) had completed post-graduate level of education, and an average, 3 (50.0%) were aged 35 to 39 years. In terms of gender, most of the KIIs, 4 (66.7%) were females.

Result (Table 3) shows indigenous food production practice by the participant’s households. Slightly above average production was reported for mangoes only as produced by 97(51.3%) of the households. Production of the other selected indigenous foods was below average. The mean land ownership was 1.14 (± 3.69 SD) acres. The mean size of land cultivated by the recruited households was 1.03 (± 1.67 SD) acres.

Information from the Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) corroborated the quantitative information regarding indigenous food production by the participant’s households. Table 4 provides a summary of qualitative data derived from content analysis. A high proportion of the FGD and KII participants reported that production of indigenous food is not fully adequate because they did not produce in all seasons.

“….the farms are small and we have accepted to transition from traditional foods into modern day foods because we have been made to believe that they have good nutrition value and fetch more profits when taken for sale in the market” (FGD1, 2022).

“……there is little focus on home-grown solutions to food insecurity in the community such as introduction of traditional foods and edible insects, which are draught resistant. Such strategies would offer sustainable solutions to food insecurity” (KII6, 2022).

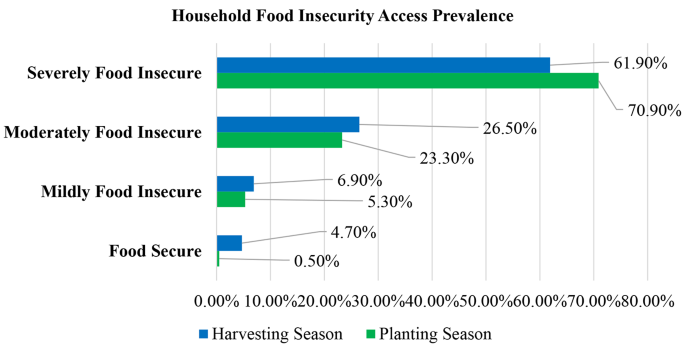

In planting season, a majority of the mothers; 134 (70.9%) experienced severe food insecurity prevalence (Fig. 1). This was also the case during harvesting season whereby a majority of the mothers; 117 (61.9%) experienced severe food insecurity prevalence. FGD participants expressed that that food insecurity was a core concern amongst the study population whereby in many instances where households run out of food or are worried that they will run out of food. The frequency of occurrence of such instances were varying depending on the stability of livelihood engagement of the household members.

“……many at times, I am worried that I may not be in a position to provide food for my households. In fact, there are times I go away from the homestead until such a time when I am in a position for provide food for them” (FGD2, 2022).

“…….providing food sufficiently on a daily basis is quite a challenge because a high number of households depend on contractual jobs; “vibarua,” which are hard to come by these days” (FGD1, 2022).

The mean weight-for-age Z score for planting season: -0.69 (± 1.06 SD) was statistically significantly higher than the mean weight-for-age Z score for harvesting season: -1.18 (± 1.28 SD) at α ≤ 0.05 (t-test, p < 0.0001). In planting season, almost three-quarters of the children; 137 (72.5%) were food secure. On the other hand, slightly more than half; 102 (54.0%) of the children were food secure during harvesting season (Table 5).

This was consistent with participant’s view that coping strategies adopted by households affected by food insecurity were likely to compromise the overall food and nutrition security of the children.

“…….household heads, especially fathers are served first so that they get energy to go and look for food for coming days. Children may be served more and women less and last” (FGD1 & FGD2, 2022).

As shown in Table 6, during planting season, production of kidney beans decreased the odds of mothers being severely food insecure by 53% (OR = 0.469, 95% CI = 0.228–0.964, p = 0.039). Mother’s food security status was not associated with production of soya beans (p = 0.233), millet (p = 0.496), sorghum (p = 0.183), cassava (p = 0.592), sweet potatoes (p = 0.567), ground nuts (p = 0.475), green grams (p = 0.226), cow peas (p = 0.556), amaranth (p = 0.583) spider plant (p = 0.640), black night shade (p = 0.782), mangoes (p = 0.426), guavas (p = 0.669), lime (p = 0.852), and tamarind (p = 0.340).

During harvesting season, mother’s food security status was not comparable to production of kidney beans (p = 0.934), soya beans (p = 0.552), millet (p = 0.812), sorghum (p = 0.097), cassava (p = 0.232), sweet potatoes (p = 0.087), ground nuts (p = 0.509), green grams (p = 0.837), cow peas (p = 0.442), amaranth (p = 0.809), spider plant (p = 0.053), black night shade (p = 0.152), mangoes (p = 0.222), guavas (p = 0.178), lime (p = 0.381), and tamarind (p = 0.382) (Table 7).

As shown in Table 8, during planting season, production of sorghum demonstrated 3.5 times increase in odds of children being severely food insecure (OR = 3.498, 95% CI = 1.454–8.418, p = 0.005). However, children’s food security status was not associated with production of; kidney beans (p = 0.741), soya beans (p = 0.430), millet (p = 0.647), cassava (p = 0.377), sweet potatoes (p = 0.210), ground nuts (p = 0.273), green grams (p = 0.328), cow peas (p = 0.247), amaranth (p = 0.644), spider plant (p = 0.997), black night shade (p = 0.708), mangoes (p = 0.671), guavas (p = 0.535), lime (p = 0.877), and tamarind (p = 0.597).

As shown in Table 9, during harvesting season, production of kidney beans was associated with a 62% reduction in the odds of children being severely food insecure (OR = 0.379, 95% CI = 0.190–0.754, p = 0.006). Children’s food security status was not comparable to production of; soya beans (p = 0.650), millet (p = 0.346), sorghum (p = 0.844), cassava (p = 0.604), sweet potatoes (p = 0.696),ground nuts (p = 0.412), green grams (p = 0.556), cow peas (p = 0.414), amaranth (p = 0.297), spider plant (p = 0.533), black night shade (p = 0.100), mangoes (p = 0.700), guavas (p = 0.334), lime (p = 0.102), and tamarind (p = 0.984).

Add Comment