Research setting and context

The study was conducted in four primary schools participating in an integrated school health initiative (ISHI) in the Marianhill area located on the outskirts of Durban in KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. We have used pseudonyms: ‘School A’, “School B”, “School C’, and ‘School D’ to represent the four schools. These schools are located in a catchment area that is characterized by widespread poverty, high HIV incidence, and poor access to basic services and facilities [15, 16]. Further, the schools receive government subsidies for school fees because of the high levels of poverty in the communities [17]. A community-based organization has been providing health and social services in the Marianhill communities. This community-based care organization has also collaborated with different stakeholders in the implementation of an integrated school health programme in some schools. The community-based organization is the main implementer of the integrated school health programme in these four schools and was responsible for hiring and managing supplementary school health nurses and school health nutritionists to assess the health of children [13].

Further, school-going children were provided meals during lunch breaks from Monday to Friday on school days as part of the national school nutrition programme. The meals children receive at schools contribute to better nourishment and health for these children. The community-based organisation (CBO) also assists some orphans and vulnerable school-going children within the communities where they provide social services. These children were also participate in arogramme called ‘kitchen soup’. The programme is implemented by a community-based organisation, and it is independent of the integrated school health programme. In this programme, orphans and vulnerable children visit the CBO drop-in centres and they receive a meal after school. However, the drop-in centres only operate on weekdays.

Research design

A retrospective cross-sectional descriptive design was adopted to examine the relationship between school-going children’s sociodemographic characteristics and their nutritional characteristics [18].

Participants and sampling

A total of 1,275 children (50.3% girls and 49.7% boys) within the age range of 3 to 15 years were assessed and screened for nutritional health conditions by school health nurses. All children from all classes who consented to participating in the initiative were screened [19]. See Babatunde and Akintola [19], for a detailed description of eligibility and screening processes.

Data collection

We collected epidemiological data by conducting retrospective chart reviews of school health screening reports and other documents. The cohort of school-going children in this study were the first batch of screening conducted by school health teams for 2017 (complete year). The school health teams comprised nurses, nutritionists, social workers, and school counselors among others, who receive appropriate training to provide healthcare. With regards to the school health nurses and school health nutritionists, WHO standard guideline for child growth as well as how to conduct anthropometric measurement of children’s nutritional characteristics forms part of their training. Meanwhile, the Department of Health also builds their capacity with regular courses and training workshops. The school health nurses provide essential healthcare to school children including regular screening. Specifically, all school-going children in the four primary schools were screened for different health conditions including: nutritional assessment, gross motor function; fine motor function; eye condition, oral health condition, ear condition, speech function, tuberculosis screening, deworming, immunisation, minor ailments, psychosocial problems and long-term health conditions. Thus, the school health team conducted a comprehensive assessment for each child on a weekly basis, completed an assessment form and also kept notes, records, and documents pertaining to the screening. The school health team comprises nurses, nutritionists, social workers, school counselors and other professionals, who may be co-opted to assist in providing some critical care [see Supplemental file used by school health nurses].

Statistical rigour

To ensure accuracy, an Excel template was used to extract the data [20]. All recorded data on the nutritional assessment forms were extracted into the Excel template., Information included demographic characteristics of the school-going children, i.e., their age, gender, grade, school, parents’ economic status, and the children’s living arrangements. We also extracted data on the children’s nutritional health status i.e. underweight, obese, at risk of overweight, stunting, wasting, severe stunting, and underweight. These measures were predetermined in the data set obtained for the study. The data extraction was conducted on all records of these children and health screening records on the children were included in the analysis. This was done to prevent selective bias and ensure a comprehensive and thorough examination of children’s nutritional status, relative to their sociodemographic characteristics. Data was double entered in Microsoft Excel sheet and cleaned for errors and missing values. The final dataset was thereafter imported into SPSS (v. 23) for the analysis.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements are noninvasive quantitative measurements used in health promotion to assess nutritional status and general health in children. It is commonly used in pediatric populations to evaluate growth, developmental patterns, and nutritional adequacy. Core elements of anthropometry include height, weight, head circumference, BMI, body circumferences (such as waist, hip, and limbs) to assess adiposity, and skinfold thickness [4, 21]. Thus, in the study schools, the school health teams received refresher training from nutritionists to prepare for the successful implementation of the school health nutrition promotion initiative. The training covered ethics, anthropometric measurements, and screening data collection, in accordance with WHO standards guidelines [22]. The children’ s weight and height were measured and body mass index-for-age and height-for-age z-scores were computed according to World Health Organization growth standards in order to determine the prevalence of underweight, overweight, obesity and stunting. Waist circumference was measured to classify the children as having a high or very high risk for metabolic disease. The school health team of trained nurses conducted the measurement and data collection. From the school health team, the children were weighed in kilograms (kgs) without shoes and jerseys using a digital portable scale. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg. Height was measured in centimeters (cm) to the last completed 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer. The same measurement protocols were used for all children. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight per square meter of height (kg/m2). The diagnosis of a child’s nutritional status (underweight, stunting, wasting, severe stunting), was based on the WHO standard reference chart booklet for: height for age, weight for age, BMI for age (see WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006 [22]). The BMI for age and sex of each child was compared with the SD “standard deviation” percentiles (z-scores) of weight for age <-2SD, weight-for-height > + 2 SD, height for age <-2SD, and BMI for age. According to the WHO Child Growth Standards, these indicators are anthropometric z scores (WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006) [22]. When the data was extracted, we followed Adedokun and Yaya’s [23] article in conducting the analysis.

Data processing and analysis

We reviewed and extracted data from all the children’s assessment forms and reports documented during the assessment process. The data already entered into the Microsoft Excel template was later imported to the Statistical Package for the Social Scientists (SPSS v. 23) for analysis. Continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were presented in frequencies and percentages. Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) test was used to assess the level of independence of the variables. Fisher’s exact test was reported for cell count of less than 5. Statistical analysis was conducted at 95% confidence interval and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We had intended to do further analysis using logistic regression modelling. However, we found that the category of interest [‘Yes’] for the outcome variables had small frequencies to support the analysis. In such statistical dilemma, Scott Long and Jeremy freeze [24] indicate that the maximum likelihood estimation including logistic regression with less than 100 cases is “risky,”and that 500 cases is generally “adequate”. Long further note that there should be at least 10 cases per predictor. Therefore, we followed Ivan Elisabeth Purba, Agnes Purba, Rinawati Sembiring [25] and Walsh et al. [26] in conducting and presenting the data analysis. Of the 21 variables in Walsh et al’s [26] study, logistic regression model was constructed for only three (3) variables that showed adequate frequencies and statistical significance (at chi-square test of independence).

Findings

We present the results on sociodemographic characteristics of school-going children and their nutritional status, using charts, frequencies, and percentages. Chi-square test of independence was also conducted to examine the level of significance of the association among the sociodemographic characteristics and nutritional status.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the children

We present the sociodemographic characteristics of 1275 school-going children. The percentage of girls to boys was 50.3% and 49.7%, respectively. Mean age of participants was 8.44 (SD = 4.94) for both boys and girls. The majority of participants were within the ages of 6 to 9 years (n = 737, 57.8%) while only 9.8% (n = 125) of the participants were age 13 years and above [Table 1]. Most children were from ‘School D’ (n = 432, 33.9%) with 14.7% (n = 188) from ’School C’. The majority of the children were in Grade R (n = 256, 20.1%). School-going children whose parents/caregivers received social grants comprised 56.5%, and 28.1% lived with both parents, 19.2% lived with other relatives, 15.2% live with one parent whilst the majority (n = 590, 46.3%) did not specify their living arrangements [Table 1]. The results on parents/caregivers’ livelihood activities showed that 56.5% (n = 722) indicated that their parents/caregivers depended on other sources of livelihood and social grants. Those whose parents were both employed (n = 136, 10.7%), both parents unemployed (n = 125, 9.8%) and either of the parents in formal employment were the second highest grouping (n = 292, 23.0%). [Table 1].

Nutritional characteristics of the children

We report results on nutrition: over and under-nutrition among the children. Out of the 1275 children’ screened, 55% of them weighed normal, 18% were at risk of being ‘overweight’, and 7% were ‘overweight’. ‘Severe stunting’ was found among 2%, 3% were underweight, whilst 3% were wasted [Table 2]. Relatedly, the ‘weight’ of the children ranged from 13 to 58 kg with an average weight of 27.15 kg (SD = 10.71). With regard to height, the children had a height range of 89 cm to168cm, with an average height of 123.83 cm (SD = 15.31) [Table 2].

Demographic characteristics and nutritional status of school-going children

Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) test was conducted to examine the relationship between socio-demographics characteristics and nutritional status of school children.

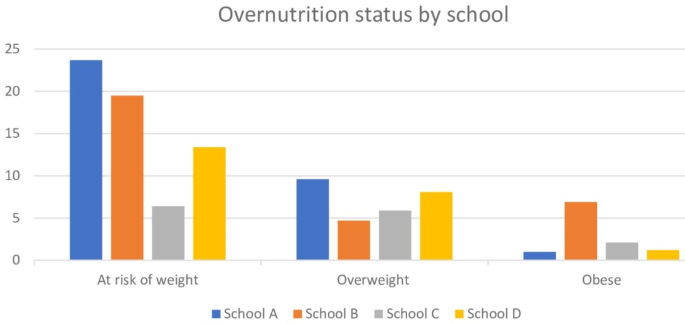

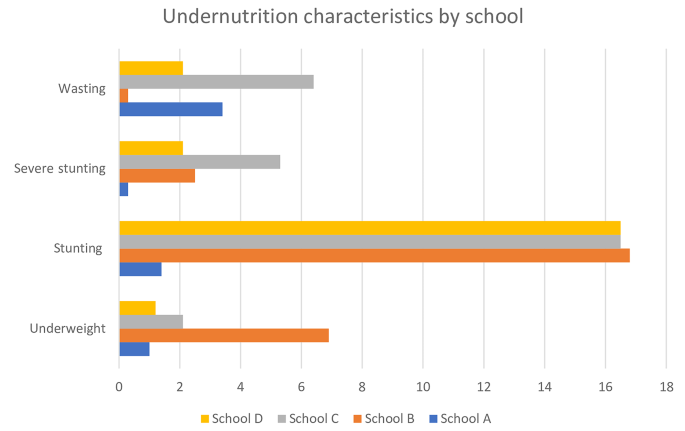

Children’s school and nutritional characteristics

The schools that the children attended had some statistically significant association with underweight (p = 0.000), at risk of overweight (p = 0.000), stunting (p = 0.000), severe stunting (p = 0.005), wasting (p = 0.010), and obese (p = 0.037). However, children from ‘School B’ primary school were significantly more likely to suffer from overweight, underweight, stunting, severe stunting and obesity compared to ’Schools A’, ‘School C’ and ‘School D’ [Figs. 1 and 2].

Age, children’s grade, stunting and severe stunting

We also found an age-group difference in relation to children’s nutritional status. Age was significantly associated with both stunting (p = 0.041) and severe stunting (p = 0.012). Prevalence of stunting increased among school-going children within the ages 3–5 (8.2%) to 6–9 (8.6%) and further to 13.7% among children within the ages of 10-12years [Table 3]. The children’s level of education was statistically associated with stunting (p = 0.037). The same pattern was observed for children who suffered from severe stunting. Highest prevalence of stunting (20.5%) was recorded among children in Grade 6 compared to children in other grades [Table 3].

Children’s living arrangement, their weight and parents’ employment

School-going children’s living arrangements had a statistically significant association with normal weight (p = 0.000), at risk of underweight (p = 0.000), and underweight (p = 0.028). It was observed that the prevalence of normal weight decreased from 62.0% for school children aged 6–9 years to 58.6% for those aged 10–12 years and further to 52.0% for children aged 13 years and above [Table 4]. Overweight ranged from 6.4 to 8.8% by age and was highest in Grade 4 at 10.5%. Children who did not specify their living arrangement were more likely to be at risk of being overweight and underweight compared to the children that lived with both parents (22.2% vs. 12.3%) and (4.4% vs. 1.4%), respectively [Table 4].

Besides, parents or caregivers’ ’employment status’ was also significantly associated with normal weight (p = 0.000), at risk of underweight (p = 0.001), underweight (p = 0.033) and obesity (p = 0.019). Children who had both parents employed were more likely to have normal weight (75.0%) compared to those who depended on social grant (55.4%). A further analysis also revealed children whose parents/caregivers were unemployed suffered wasting (7.2%) compared to children who had both parents employed (1.5%). However, the social grant to parents/caregivers showed some positive effects on the number of children who had normal weight (55.4%), wasting (1.0%), underweight (4.0%), ‘at risk of overweight (20.2%)’ [Table 3].

Add Comment